Within minutes, they were at the scene—or what was left of it—battling falling debris and braving waves of dust. They kicked off their heels and ran barefoot toward the Twin Towers while everyone else was trying to escape. They slept in news trucks and did live reports from hospital beds to let the world know what happened; to make sure no one would ever forget. Now, as the 20th anniversary of 9/11 approaches, ELLE sat down with 10 female journalists who reported on the ground in New York City, Washington D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania. For many of these women, talking about that day is just as emotional as it was two decades ago—but as former NY1 anchor Kristen Shaughnessy said, “We owe it to the people who were killed to continue telling this story.”

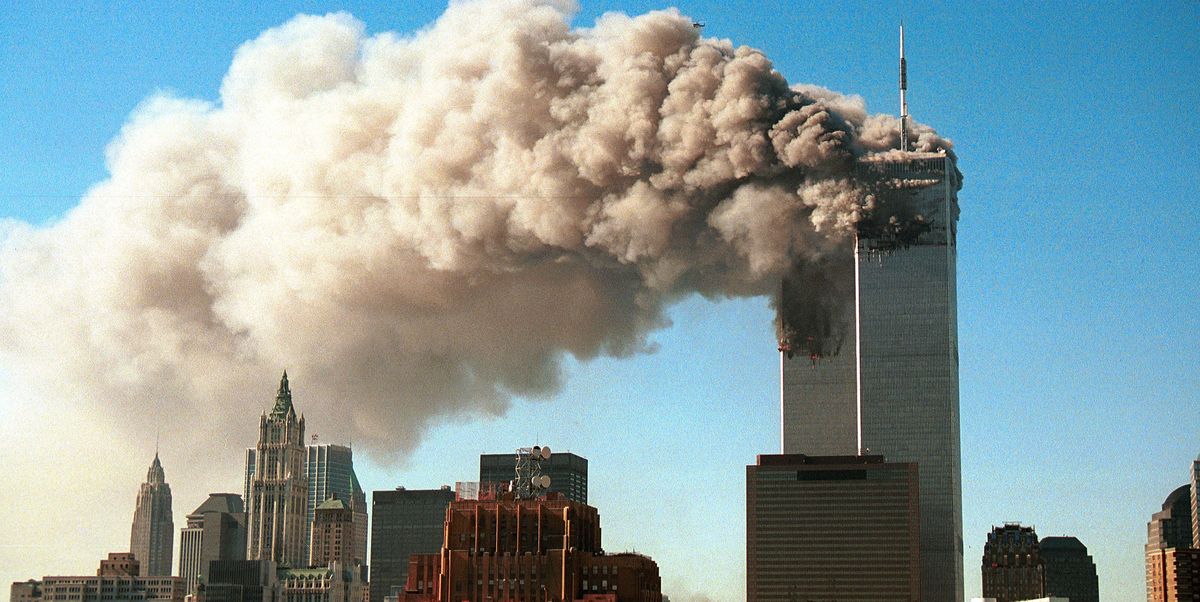

At 8:46 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of New York City’s World Trade Center. CNN’s Carol Lin, the first national news anchor to break the story, thought it “had to be an accident.” But when a second plane, United Airlines Flight 175, hit the South Tower, Lin—and the rest of the country—realized America was under attack.

Carol Lin, former CNN anchor: In my earpiece, my executive producer told me, “We have a report of a plane going into the World Trade Center. Get to the main anchor set. We’re going into rolling coverage.” That means you drop the scripts, the teleprompter goes blank, and you go into indefinite live coverage. On the preview monitor, there was the North Tower of the World Trade Center with a big gaping, smoking hole in it. I thought this had to be an accident. But how is it an accident when you have a large passenger jet crash into the World Trade Center on a beautiful, crystal-clear fall day in New York? It seemed inconceivable. It wasn’t until the second plane hit that we knew we were in the midst of a terror strike on the United States.

Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC’s Morning Joe co-host: I was trying to fit in at my new job as a CBS correspondent, so I was wearing a wine red skirt and jacket and black pumps that day. I tried to get a cab to the World Trade Center, but it was total gridlock. So I literally found myself hiking the skirt up and full-out sprinting down the West Side Highway while holding my shoes.

Sofía Lachapelle, former Telemundo and Univision reporter/anchor: We were going into the chaos, while everyone else was getting out. I looked up and realized we were right where everybody was jumping. It was a feeling of frustration, because you want to do something—you want to extend your arms and hold these people.

Barbara Starr was working at the Pentagon when a third plane, American Airlines Flight 77, flew into the west side of the building. As “massive flames” engulfed a nearby corridor, Starr rushed to the site of the crash and began reporting.

Barbara Starr, CNN Pentagon correspondent: September 11th is my birthday. I woke up around 6 a.m. in a great mood, and it quickly got better. I looked out the front window and saw the weather was great. I didn’t have plans, but thought I’d ring a few reporter friends and see who might be getting out of work early. I was working as the Pentagon producer for ABC News, and I was making my usual checks, talking to folks, making sure nothing newsworthy was going on—and a horror was forming just over the horizon. A Pentagon police officer ran down the press corridor yelling, “We’ve been hit! Everybody get out!” The plane had burst into massive flames just a few corridors away. I learned that day you operate by instinct and never really know until afterwards if you made the right decision. This time, I did. I went out the door, turned left and was at the attack site, able to report on what I saw. I watched as first responders from all over the region suddenly came rushing in, trying urgently to get the fire under control and rescue the wounded and those trapped in the wreckage—and to tend to the dead.

Amna Nawaz, PBS NewsHour chief correspondent: I was a 21-year-old fellow with ABC News Nightline in Washington, D.C. As a kid, looking at the adults in the room—as worried and confused as they were—made me panic. Producers in their offices were crying on the phone, trying to reach their own loved ones. I was a deer caught in headlights, running every direction, making copies, calling this person and seeing what I could find out, getting this piece of tape. The fear was palpable. There was so much we didn’t know. I saw how in those moments, when it feels like everything is swirling around you and you have no idea which way is up, the facts matter. It felt like a mission, like a service.

Hijackers took over a fourth plane, United Airlines Flight 93, which began flying in the direction of Washington D.C. Passengers and crew attempted to take back control, and the plane crashed in a field near Shanksville, PA. One of the first reporters on the scene was Cindi Lash of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who calls that day 20 years ago “so emotional.”

Cindi Lash, Pittsburgh Community Broadcasting Corporation/WESA executive editor: I was working as a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter, and we got a heads up at the local news desk that there may have been another crash in Somerset County, east of Pittsburgh. My colleague and I grabbed our notebooks and laptops and went off. Driving out to the crash site, we weren’t seeing any ambulances coming back from the scene. I knew then no one had survived. I ran into a couple of state troopers and asked one, “How bad is this?” He just shook his head. When it became very clear this was going to be a long-term reporting situation, my husband and my colleague’s wife threw together overnight bags for us, and my husband drove them to the crash site. My younger son, in particular, was really worried that I was at this plane crash, so my husband brought our boys with him. They were able to see me and know I was all right—but watching them drive away to go home was the worst moment of my life. It still wasn’t clear what was happening. Are we at war? Is somebody going to drop more bombs on us? I was so emotional, because I didn’t know what could happen next.

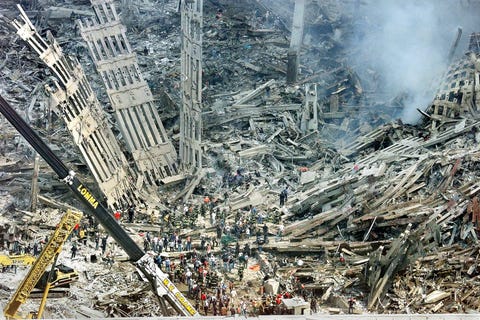

Within two hours of being hit, both 110-story World Trade Center towers had collapsed, coating the air with a dangerous layer of dust and debris. Photojournalist Ruth Fremson of the New York Times sought refuge from the suffocating plume in a deli, where she stayed until it was safe to come out.

Carol Marin, former CBS News correspondent: The ground began to move and rumble. I ran, and I fell. A firefighter picked me up by my waist, threw me on my feet, and pushed me under the overhang of a granite building, covering my body with his. I could feel his heart pounding against my backbone. The firefighter handed me off to a New York City police officer who took my hand, and we walked through the cinders and smoke.

Kristen Shaughnessy, former NY1 anchor: As a reporter, you’re supposed to stay and get the story. But in that moment, you really had no choice but to run. It was coming down pretty quick, and you were getting chased by that plume.

Ruth Fremson, New York Times staff photographer: It just was this whoosh of grit and dust. I opened my eyes, and it felt like somebody was grating sandpaper across them. Instead of crashing, things started landing softly all around us—thud, thud, thud—because of all the dust. All I saw through this white haze was this one tower shining in the sun. As things settled, we made our way to a deli. We started helping ourselves to the water in the deli case and just spitting out mouthfuls of mud. I started taking pictures of the people who were stumbling in. When I made my way back outside, one of the firemen said to me, “I wouldn’t go too far. The other one might come down, too.”

Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC’s Morning Joe co-host: We took shelter in a school, which became a place where the firefighters and cops were coming in to get water, catch their breath, and then they turned around to go right back in. They were unbelievable. There was no resting. A few of them got on the phone, saying, “Please tell my wife I love her,” and then walked back in the tower. I’ll never forget this one firefighter’s face; he just knew he wouldn’t see the light of day again.

Allison Gilbert, author and host of the documentary series Women Journalists of 9/11: Their Stories: We ran into a makeshift triage center where I was told by a police officer to make myself vomit to make sure all of the debris could leave my body. You could feel the second tower underneath your feet, the rumbling of the floors beginning to pancake. I thought the tower was going to fall like a tree, and I was going to try and outrun this falling skyscraper, not realizing that it was just going to implode. I’d worn slip-ons that day to cover the primary election as a producer at WNBC-TV. Instead, I ran right out of my shoes. I wasn’t dressed for war.

Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC’s Morning Joe co-host: Before the building collapsed, my colleague and I saw people jumping. I kept saying, “Look at that, it’s pieces of glass.” He had to correct me and explain that the flickers I saw were people. I don’t think my brain was really processing. When the second building went down, it was like The Day After, that movie where the place had been nuked. It was like walking on the moon.

Journalists all across the country made it their mission to chronicle the unimaginable tragedy—often prioritizing the story over their own safety. After a near-death experience at Ground Zero, Allison Gilbert was rushed to Bellevue Hospital in New York City, where she did a live report after being treated in the emergency room.

Allison Gilbert, author and host of the documentary series Women Journalists of 9/11: Their Stories: I was taken to Bellevue Hospital where doctors cut off my clothes to make sure I wasn’t impaled and tubes were put down my throat to help me breathe. After a while, they transported me to a different room and the tubes were removed. I asked any nurse that came in to give me a landline so I could call into my newsroom, not only so my colleagues knew I was alive, but to get on the air. I ended up doing a live report from the hospital.

Sofía Lachapelle, former Telemundo and Univision reporter/anchor: We got trapped inside a truck, but I’m assuming because I’m alive that we were not trapped under too much debris. An officer helped get us out, and one of our photographers with me said, “You know what, guys? If we’re going to die, we’re going to die doing what we came here for. Can you continue?” Some people will quit the job and go. We didn’t have that state of mind. So I continued with the live on tape.

Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC’s Morning Joe co-host: In the school, I found these huge boots in a garbage can, which I pulled out and wore for five weeks after that. Somehow, I also found a phone. I was shaking as I dialed the CBS newsroom.

Carol Marin, former CBS News correspondent: I went to the broadcast center, with my hair and clothes covered in dust, and a producer threw me on set with Dan Rather. He held my hand, because I choked up trying to tell the story as coherently as I could, mindful that I’d survived to tell it. I ended up working that whole day and late into the night. It was only when I took a shower later that I realized I’d lost some of the skin on my toes from kicking off my shoes to run barefoot down the street.

Cindi Lash, Pittsburgh Community Broadcasting Corporation/WESA executive editor: That night, my colleague and I stayed at my friends’ house, who lived nearby. I got in bed—and this has happened to me a couple other times when I’m covering a breaking disaster—and started to twitch with muscle spasms. After about three hours, I could hear my colleague stirring; he couldn’t sleep either. So we both just got up and put clean clothes on and went back to the site.

In the days and weeks following 9/11, journalists worked overtime to help the world make sense of this catastrophe. For journalist Amna Nawaz, who recalls being the “only Muslim in the newsroom” at the time, it was a wakeup call for why someone like her needed to “be in this conversation.”

Barbara Starr, CNN Pentagon correspondent: Everybody simply did their job. We reported the news. The Pentagon never shut down, and everyone who could came right back to work the next day amid the wreckage.

Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC’s Morning Joe co-host: All you could do for people was cover the stories of their loved ones who were lost. They wanted people to know about this person they loved so much, because they had nothing to show. No bodies. Nothing. The thing that drove me was telling these stories, because it was something you could do in a time when there was nothing you could do. It gave me purpose.

Carol Marin, former CBS News correspondent: We interviewed the children of the stock firms and traders that filled those towers. We were in the houses of widows over and over again, people who were shell-shocked and gasping for some way to reason with this. They were so traumatized, yet they wanted their loved one remembered. That’s why they were willing to have those agonizing conversations.

Carol Lin, former CNN anchor: The first instinct of every journalist is to be where the story is happening. My objective was to make sure I volunteered to go overseas. While I was anchoring these six-hour rotations after the crash, I was also working on getting my paperwork ready. Being a female, I couldn’t enter Afghanistan, but I got as close as I could: the city of Quetta in southern Pakistan, right on the Afghan border. Other than a rare female journalist, I didn’t see another woman for months. I always had to work through an interpreter, because men would not make eye contact with me. I wanted to understand how much control Pakistan had over the border, because to control the border was essential to control the flow of Taliban fighters going back and forth.

Cindi Lash, Pittsburgh Community Broadcasting Corporation/WESA executive editor: We worked day in and day out at the crash site for the next two weeks. Family members and friends were expressing to us that they were concerned their loved ones’ lives were getting lost in the larger picture, that the Shanksville crash, as awful as it was, was being dwarfed by the coverage of the Twin Towers and the Pentagon. It carried a lot of weight with us, and we put together a team to profile all 40 of the passengers and crew on the plane. This was a sacred task for us. When people are willing to trust you with their stories, that’s a tremendous responsibility. We reached out as gently as we could, because we knew how battered people were. In order to try to profile these people, they had to become real to us. Their loved ones spent a lot of time with us, painting a picture of what their person was like. Once you build that in your head and in your heart, it’s not like those people go away.

Amna Nawaz, PBS NewsHour chief correspondent: I was the only Muslim in the newsroom, and I had a lot of older, white colleagues asking me all kinds of questions about my faith, like: What does this word mean? Were you ever taught about jihad? Does the Quran really say this? There was such a lack of understanding, and that led to suspicion and scrutiny and animosity. I saw how necessary it was for someone like me to be in this conversation. My parents are originally from Pakistan. We spent a lot of time there growing up, so I’m deeply connected to the region. We had a meeting in the newsroom at one point where people were casually talking about war and dropping bombs and casualty numbers. I thought, that’s my family over there. I was so upset, I had to leave the meeting. Ted Koppel called me into his office later that day and asked if I was okay. I just started to cry. I was so scared and upset, and I didn’t know what was going on. All I kept thinking was, I can’t believe I’m crying in front of Ted Koppel.

For many journalists, the weight of the attacks—and the gravity of the reporting—took a toll. Former Univision anchor Sofía Lachapelle left the industry for seven years after a months-long stint at Ground Zero. “I developed post-traumatic stress disorder and had panic attacks,” she says. “You can play with everything, but not with your brain.”

Carol Marin, former CBS News correspondent: At the time, I was training for a marathon. One day, I was trying to run along the lakefront in Chicago when a plane came in for a landing. I felt myself panic before I could process that the plane wasn’t going to hit a tower. Another time, I was downtown when a wrecking ball took down a building. There was this big explosive crash, and I jumped. I was frightened before I could process what was going on. There were all these triggers that would terrify you, because you’ve now seen something worse. It slowly receded over time, but it really taught me something about the aftermath of living through something so shocking, so traumatic.

Amna Nawaz, PBS NewsHour chief correspondent: I used to wear a prayer ring with Arabic script that my grandmother gifted me. I turned my ring around so people wouldn’t look at it. A lot of our friends kept their kids home from school, because they didn’t know how they’d be treated. We had family members who were named Osama; imagine what that was like at the time. Every single one of the families we knew, including mine, hung an American flag outside the house, because suddenly you had to prove to everyone that you were not a threat, that you were just as American as everyone else. I’d never been made to feel that way before.

Carol Lin, former CNN anchor: 9/11 began a series of events that made me realize life is short and precious, and personal decisions I had delayed became more important to me. It was when my husband and I decided to have a child; we decided, it’s now or never. Then after, my husband unfortunately died from cancer. His death had nothing to do with the attack, but I think that day prepared me to understand tragedy on a deeper level and have a greater appreciation for life and change. 9/11 really prepared me for what was going to come in that next phase in my life.

Sofía Lachapelle, former Telemundo and Univision reporter/anchor: By November, I was feeling sick and tired. I hid it, because when I was on the air, I looked fine. But off air, I was weak and coughing all the time. I developed post-traumatic stress disorder and had panic attacks. You can play with everything, but not with your brain. My work gave me one year of medical leave, and I also made the decision to leave New York. I stayed at a farm that belongs to my family, and took care of myself surrounded by nature. I disconnected from the news world completely.

The journalists who were there remember and pay tribute to the heroes who saved so many lives. Now, as the future of Afghanistan hangs in the balance, many of the women ELLE spoke with find themselves wondering: What did we do the last 20 years?

Sofía Lachapelle, former Telemundo and Univision reporter/anchor: I held onto the jacket I was wearing that day for a long time. I threw it in the garbage can many times, but always went back and grabbed it. “Somebody might need this one day,” I said to myself. And guess what? I was right, because many years later, I gave it away to the 9/11 Museum. I still feel guilty sometimes, like, “Why am I so special that I have to be alive and all these people died?” But I’m more mature now, and my emotions are in a better place.

Carol Lin, former CNN anchor: I look at my daughter, and I think about the world that she’s entering. Is it safer? Are we better? But I am so thankful for the people who felt that on such a terrible day, they had a source of information they could trust. It’s essential to our democracy that if, or when, we have another catastrophic event, we understand there are people who are trying to honor this profession and get the facts out.

Ruth Fremson, New York Times staff photographer: I don’t like to revisit 9/11. It was traumatic. I did my job, but it felt very weird when we won the Pulitzer for that. It’s nice to be recognized for doing good work, but it’s horrible to be recognized when it’s because of somebody else’s tragedy.

Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC’s Morning Joe co-host: My life leading up to 9/11 was one life, and my life after was another. I still find it hard to talk about it. Whenever I see a rich, brilliant blue sky, I think of that day—it will never just look like a blue sky to me again. It also really hurts to be talking about it given what we’re witnessing now in Afghanistan. I’m especially thinking of the women there.

Amna Nawaz, PBS NewsHour chief correspondent: The fact that a presidential candidate proposed banning all Muslims from entering the country and ended up winning the election tells you everything you need to know about how Muslims are seen in America today. There’s still a sense that you have to prove you’re not a threat. There are periods in which the hate messages come and go, but it’s always there, just waiting for a spark to light it again. There’s also a whole foreign policy discussion we can have around what’s happening in Afghanistan. This is a moment of reflection for all of us as Americans to ask: What did we do the last 20 years? What was it all for?

Kristen Shaughnessy, former NY1 anchor: I used to hesitate talking about 9/11, but here we are 20 years out, and there are people who weren’t even born yet. They don’t know what happened. We owe it to the people who were killed that day to tell this story.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.