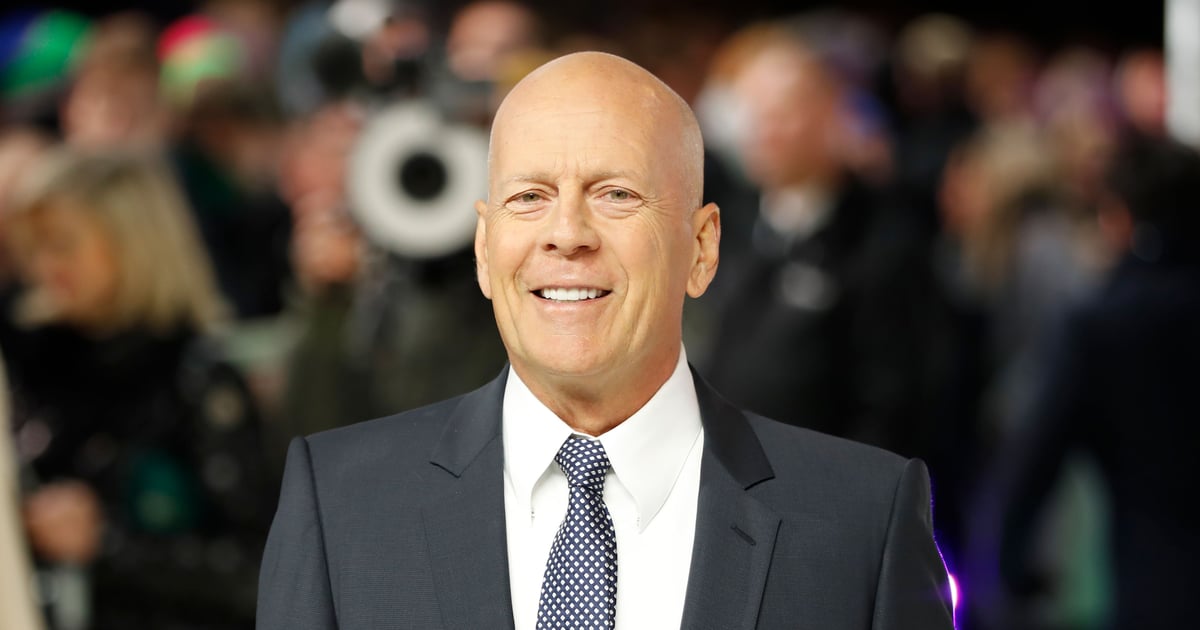

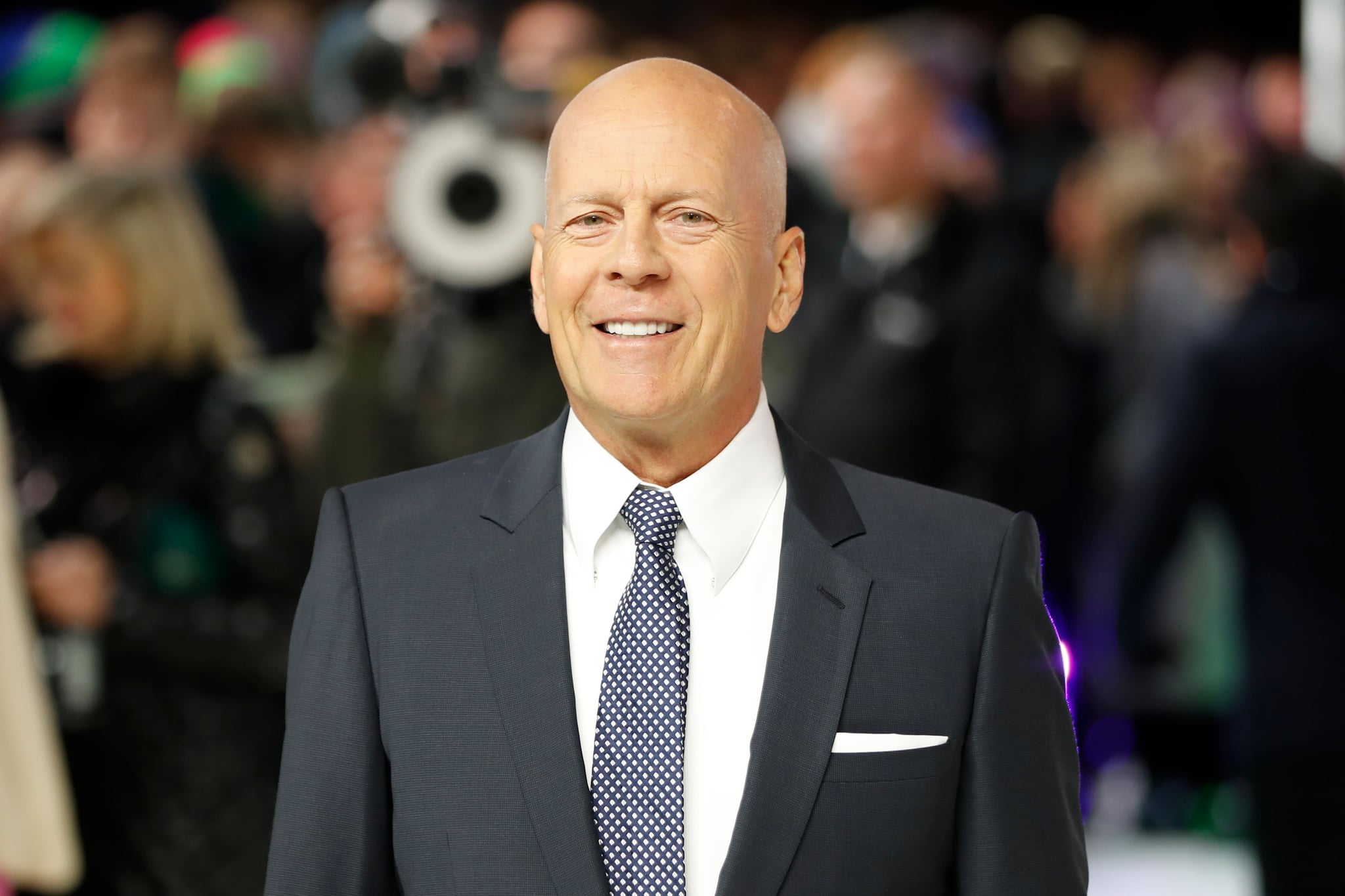

Tough news hit the entertainment world today as Bruce Willis‘s family announced he will retire from acting after being diagnosed with a language disorder called aphasia. The condition is “impacting his cognitive abilities,” his family members wrote on Instagram. “As a result of this and with much consideration Bruce is stepping away from the career that has meant so much to him.”

Aphasia affects two million Americans, according to the National Aphasia Association (NAA), but a 2016 survey from the organization found that less than nine percent of respondents knew what the condition even was. Though it’s not a disorder that’s talked about much, Willis’s announcement is bringing new attention to aphasia and its impact on patients and their loved ones. Here’s everything you should know about this condition, including symptoms, causes, and treatments.

What Is Aphasia? Symptoms and Causes

“Aphasia is the inability to communicate or speak,” May Kim-Tenser, MD, neurologist with Keck Medicine of USC, says. Aphasia presents in different ways (see below), but the condition can affect all aspects of communication: speaking and understanding spoken word, as well as writing and reading.

“Usually aphasia occurs after a stroke, and it’s pretty sudden in onset, or it can occur after a head injury,” Dr. Kim-Tenser says. Aphasia may also come on gradually from a slow-growing brain tumor or a degenerative disease, such as dementia. “Usually [aphasia caused by those conditions] is chronic and happens over time,” Dr. Kim-Tenser explains. “If you see aphasia that happens all of a sudden, it’s usually due to a stroke.” Because of the relationship between strokes and aphasia, people with risk factors for stroke (including high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol) are also at higher risk for aphasia. Older people, especially people over the age of 65, and those with a family history of stroke are also at higher risk.

Though all types of aphasia affect language, specific symptoms vary between people and forms of the condition. The NAA recognizes several different types, including the following.

- Global aphasia: This is the most severe form of the condition. Patients with global aphasia can produce “few recognizable words,” are able to understand little to no spoken language, and cannot read or write.

- Broca’s aphasia, or nonfluent aphasia: Patients with Broca’s aphasia may be able to read and understand speech but have severe difficulty with speech and writing.

- Wernicke’s aphasia, or fluent aphasia: This form of aphasia impairs the ability to write, read, or understand speech. According to the NAA, patients with Wernicke’s aphasia can produce “connected” but abnormal speech interspersed with irrelevant words and confusing sentences.

- Anomic aphasia: People with anomic aphasia have a persistent inability to find the exact word they’re looking for, especially nouns and verbs. This goes for both speaking and writing, although they can typically read and understand speech.

- Primary progressive aphasia: This form of aphasia is caused by neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, and is characterized by a slow, progressive impairment of communication ability.

Is Aphasia Treatable?

Treatments for aphasia vary based on the cause of the condition, Dr. Kim-Tenser says, but typically involve speech and language therapy. Patients “need to relearn and practice language skills,” she explains. Depending on their type of aphasia, they may also learn other ways to communicate. Techniques might include writing but not necessarily verbally communicating the language or using a board with letters, Dr. Kim-Tenser explains.

It’s important to remember that aphasia that comes on suddenly can be both the result of stroke or a sign that a stroke is occurring. If you notice that you or someone else is suddenly struggling to speak coherently, call 911 and go to the emergency room, Dr. Kim-Tenser says. If it is an acute stroke, “we do have acute treatments that can potentially reverse the aphasia,” she explains, including clot-busting medications or surgically removing a clot in the affected blood vessel.

For those affected by long-term aphasia either personally or with a loved one, frustration over communication is common, Dr. Kim-Tenser says. Some patients are just not able to communicate what they’re trying to say. “There’s a lot of patience that needs to be had,” she says. Dr. Kim-Tenser also notes that aphasia support groups and stroke support groups (for those whose aphasia was caused by a stroke) are available for patients and their families.