Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

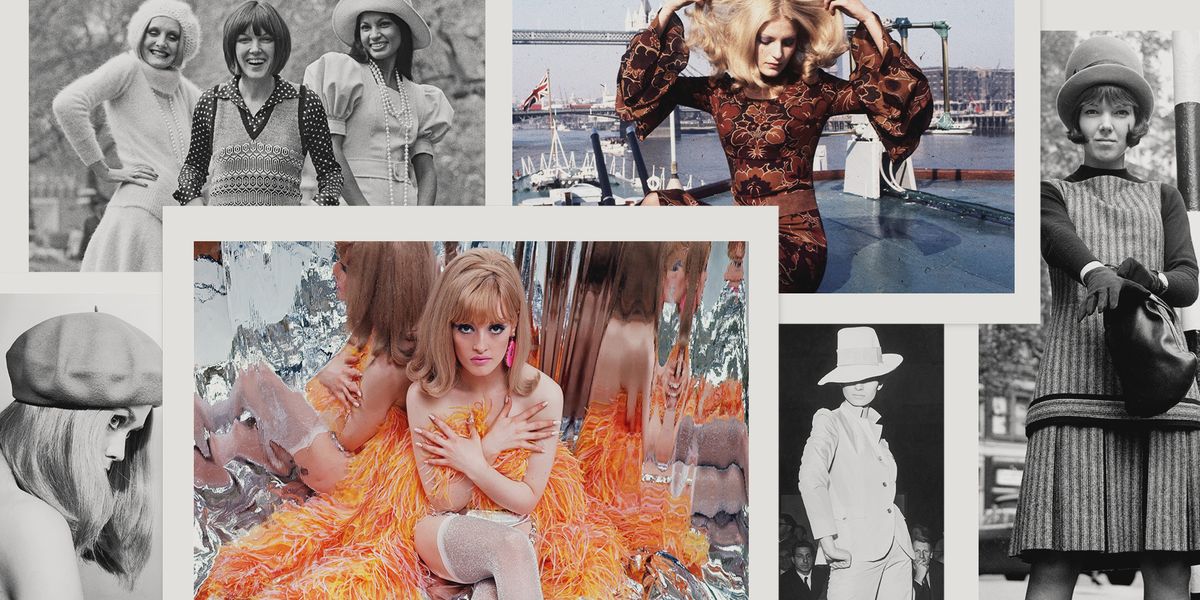

“Is this just another fad?” asked one Mary Quant ad, in a self-aware nod to the way the brand was often dismissed as a passing trend. But if you’ve ever worn a miniskirt, thrown on a pair of hot pants, or even applied waterproof mascara, you know Quant was anything but. When the designer, who died today at 93, burst onto the scene in the mid-1950s, fashion was still stuffy, starchy, and decidedly grown-up. By the time she and her cohorts were done with it, style had loosened up—along with the culture around it. (“Good taste is death, vulgarity is life,” she once said.) Quant’s era played host to a seismic fashion shift; no wonder they called it the Youthquake. The grand dame was dead, and the freewheeling young woman was fashion’s new muse.

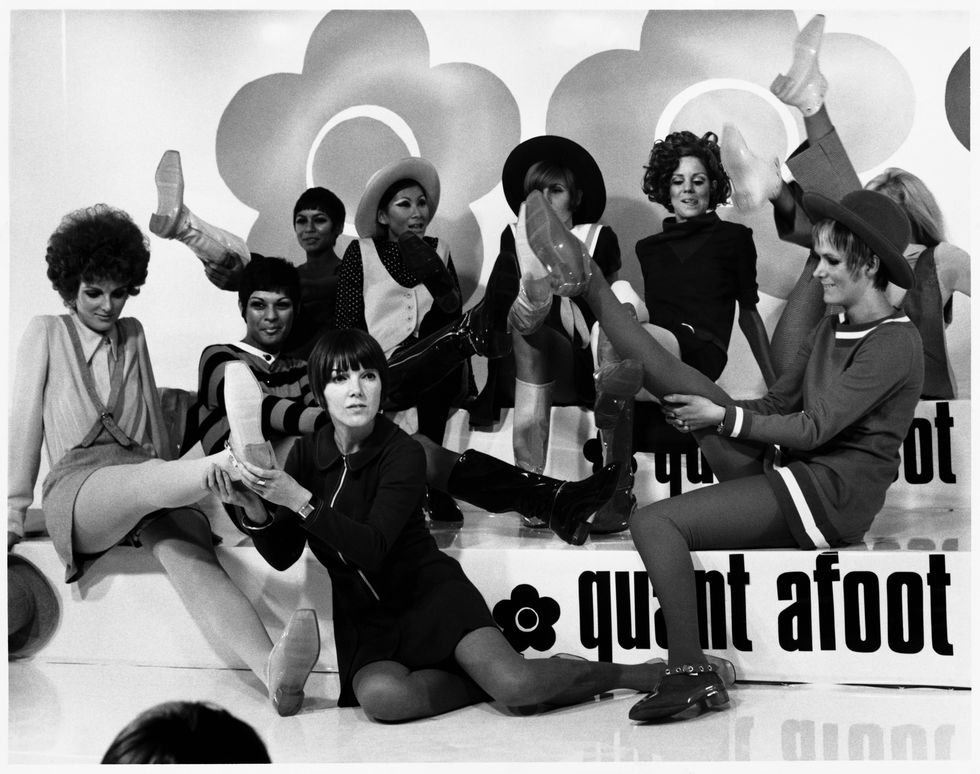

Quant’s Chelsea boutique, Bazaar, which opened in 1955, was one of the most influential stores of its time, and a beacon of colorful optimism in still-bleak postwar London. Onlookers were shocked by the hemlines, but customers were on board. The store catered to the so-called “Chelsea Set,” and notables like the Rolling Stones and Brigitte Bardot were known to pop in.

Quant’s rise intersected perfectly with the growing movement for women’s liberation. While her designs bared plenty of leg, they didn’t feel as objectifying as their more covered-up ’50s counterparts. They had a colorful, youthful quality that was inspired by playclothes, complete with Peter Pan collars and A-line shapes. The newfangled stretch fabrics she favored freed the wearer from constriction; pockets added convenience. Her looks were often accessorized with colorful tights and flat shoes. Quant said she wanted to create designs that women could “run to the bus in.”

Most importantly, they were affordable, democratizing fashion for a generation fed up with the trappings of their mother’s wardrobes. Her customers were increasingly entering the workforce (and nightlife), in droves, and wanted to look as youthful as they felt. Quant dressed icons of the decade like Twiggy, Pattie Boyd, and Jean Shrimpton, and designed looks for Audrey Hepburn, a past Bazaar customer, in Two for The Road, and Charlotte Rampling in Georgy Girl.

Quant helped popularize the miniskirt (which she named after that other ’60s sensation, the Mini Cooper) and she was her own best model. “I wore them very short and the customers would say, ‘shorter, shorter,’” she once remembered. In the late 1960s, she introduced the even more daring hot pant. The ultra-abbreviated style, she said, “sold faster than (they) could make them.”

Quant also made her mark on the makeup world. Her cosmetics line, with its daisy logo and colorful crayon formulations, shared the same sunny, childlike outlook as her fashion. And she brought the world a truly innovative invention: waterproof mascara.

We may not be donning PVC shifts and go-go boots much anymore, but the free-spirited mod trend continues to dominate the runways season after season. Quant’s influence lives on, and her vision of female freedom still feels as fresh as it did back in 1955.

ELLE Fashion Features Director

Véronique Hyland is ELLE’s Fashion Features Director and the author of the book Dress Code, which was selected as one of The New Yorker’s Best Books of the Year. Her writing has previously appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, W, New York magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, and Condé Nast Traveler.