The best scary movies hold up a mirror to society—perhaps that explains why Bodies, Bodies, Bodies, the latest cool-kid horror film from A24, has become an immediate sensation. Set at a palatial country house amid a coming storm, the satirical film follows a group of vicious, privileged 20-somethings who converge at their friend David’s (a perfectly cast Pete Davidson) parents’ McMansion for a “hurricane party.” As the rain sets in, the group decides to play Bodies, Bodies, Bodies—a party game where a player selected as the “murderer” must tag and “kill” a victim, at which point the whole group must ferret out the killer among them—but the festivities go from merely tense to terrifying as the friends begin to actually die one by one.

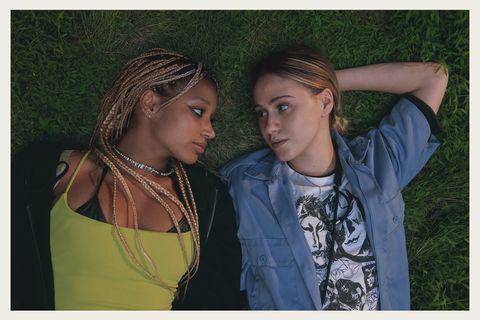

For director Halina Reijn, the party game—and the things it reveals about the characters playing it—was half the appeal of the film. “I have a tight friend group, and we used to play that game,” says the Dutch filmmaker. “[Whether] you call it Mafia or Werewolf or Murderer or whatever, it would always be a complete disaster. Everybody would fight each other, and it would be total psychological warfare, and all these secrets would come out.” Indeed, almost as soon as Sophie (Amandla Stenberg) suggests they play a round, the others are quick to object, pointing out that the game dissolves into tears every time they play. The backlash probably isn’t helped by the fact that, although Sophie has clearly known the rest of the friends since childhood, she doesn’t seem to be entirely welcome at the mansion. Plus, she’s brought along her girlfriend of six weeks, Bee (Maria Bakalova), without asking permission—never mind that Sophie’s ex-girlfriend, Jordan (Myha’la Herrold), is among the group gathered there.

The characters’ uneasy camaraderie is outdone only by the actors’ obvious affection for each other in real life. “I don’t know if it was just the way we were in this random hotel in this little town [or just] the trauma bonding of making a movie,” says Rachel Sennott, whose party-girl character Alice has showed up to the house with her brand-new 40-year-old boyfriend Greg (Lee Pace) in tow. “[But by] the end of the first week, we were shooting that scene in the gym with Greg, and it was such an intense day, and we were all just sleeping on each other when we literally met each other a week ago.” Bakalova agrees. “We clicked pretty quickly,” she says. “We pretty much trauma bonded immediately because we had these huge rain-wind machines, we had blood, mud, and everything that you can imagine—it’s like the end of the world is coming.”

The film is a classic whodunnit slasher, keeping you guessing until the very end as to who’s responsible for the killings. As the hurricane approaches, the characters down shots and pop pills; by the time tragedy strikes, then, sobriety and mindfulness are already distant memories. (The one exception is Sophie, who is freshly out of rehab—though she’s not exactly the healthiest decision-maker of the bunch to begin with.) With each new death, the group becomes more and more paranoid until the lifelong friends are all accusing each other of multiple murders. Like many horror movies, Bodies, Bodies, Bodiesseeks to make a broader statement about good and evil. Tellingly, however, everyone involved in making the film has a different opinion on who, or what, the “real” monster is. To Reijn, the true villain is the feral, Lord of the Flies-esque groupthink that takes over the characters—just as it can also affect all of us, no matter how sophisticated we think we are: “Are we beasts or are we civilized? What does it take for us to become an animal again, and how little is necessary?”

The cast members think otherwise. Chase Sui Wonders, who plays David’s picture-perfect girlfriend Emma, makes repeated references to the “posh prison” of the setting. (“The gaudy mansion, where if you look too closely it’s just so tacky and gross—it’s all nightmarish,” she says.) Sennott cites the group’s “hysteria and paranoia” as their downfall, while Stenberg singles out the wealthy characters’ extreme—and painfully unexamined—privilege as the source of the film’s evil. Bakalova, meanwhile, contends that the biggest menace of the story is “the lack of trust and the lack of honesty that these people have. They call each other friends, and they say that they love each other, but they actually do not really know each other at all.”

They call each other friends, and they say that they love each other, but they actually do not really know each other at all.

Even so, there’s one malevolent force that everyone agrees is at least partly to blame: social media. Like so many of us, the characters of Bodies, Bodies, Bodies are more concerned with saying or doing the “right” things in front of an audience than with actually figuring out how to be good people. (During a particularly tense moment when the surviving characters are terrified for their lives, Sennott’s perennially unhelpful Alice turns to Sophie—a queer, Black recovering addict—and shrieks, “I’m an ally!”) “A big part of it is: how people will treat us, what people will think about us if we do not really fit into the norm of ‘this is good’?” says Bakalova. The glare of social media makes it hard to distinguish the pursuit of bettering ourselves from that of bettering others’ opinions of us—as Reijn puts it, “It used to be just actors growing up front of cameras, but now everybody grows up in front of cameras.”

The result is a culture where performative “goodness” carries more weight than anything we do when others aren’t watching. The friends at the core of Bodies, Bodies, Bodies have fully bought into that worldview: in a scathingly clever indictment of social justice-obsessed internet culture, the script by Sarah DeLappe is chock-full of wellness-oriented internet slang like “safe space” and “toxic,” and the characters relentlessly fling accusations of “triggering” and “gaslighting” at each other. They pride themselves on “virtue signaling” and out-woking one another. Even under life-or-death stakes, they can’t turn off their hyper-awareness of how they’re being perceived—and that’s what “gets in the way of actually finding out what happened,” Herrold says. “Like so many others in this time, they’re treading this new infrastructure of accountability so gingerly and with so much fear, while also failing deeply to see the ways in which they embody the things that they say that they don’t,” says Stenberg. Perhaps it seems ironic that a movie about the horrors of social media would take place largely in a shuttered house with no electricity, phone, or internet access, but—Stenberg argues—that’s the point. “There’s such a small gap between the experiences that we have and then the relationship that we have now to broadcasting those experiences in a presentational way to the world, so once that element is taken away where the internet is gone and there’s no invisible audience, then it’s revealed that the basis of [these characters’] relationship is quite fragile.”

The fact that there are large swathes of people who believe that they are somehow exempt from interrogating their own racism and sexism and misogyny…like, that’s hilarious to me.

Just as fragile are their relationships to themselves. It’s clear that David, Emma, Sophie, Alice, and Jordan no longer know each other as well as they did when they were growing up together, but one thing they still have in common is that they “are definitely deeply afraid of acknowledging their own privilege,” says Stenberg. As far as she’s concerned, that’s where the movie’s humor comes from. “The fact that there are large swathes of people who believe that they are somehow exempt from interrogating their own racism and sexism and misogyny because their intellectualism makes them feel like they are exempt from interrogating themselves—like, that’s hilarious to me.” As an outsider, not just to the friend group but also to their entire socioeconomic class, lower-class immigrant Bee’s presence illuminates the gap between who these rich kids say they are and who they actually turn out to be.

Take David’s girlfriend Emma, for example. “She’s incredibly image-conscious,” says Wonders of her character. “She’s talking to the new girl and being really nice and putting on a smile, but then not having awareness of how unwelcoming and unfriendly she can be. It’s just funny the contradictions that exist with people who are constantly trying to be at the helm of all these issues and topics, when in fact, boots on the ground, it’s not necessarily the case [that you’re] tolerant of the person sitting next to you.” Or consider Herrold’s hostile, wounded Jordan, who prides herself on not being as insanely privileged as her friends: she’s only upper middle-class, after all. “I just think that she wants to be better than them,” says Herrold. “I think she fears being perceived as one of them, so she takes on a way of being so that visually it doesn’t seem like she’s like them, but she is a lot like them.”

Though it’s difficult to fully explore without spoiling the plot, that sense of duality turns out to be key to the whole film. Bodies, Bodies, Bodies isn’t just a horror movie about saying one thing and doing another. It’s also about the difference between our intentions towards the people around us and the impact we actually have on them: Even the most well-meaning decisions can have disastrous consequences. In that sense, we all have the capacity to be “both good and evil, just depending on the circumstances,” according to Bakalova. Impressively, the film strikes a careful balance between attacking “cancel culture” and the internet’s collective obsession with wokeness without attacking the good intentions that typically drive it. “The point isn’t to shit on Gen Z and say they’re so vapid and stupid. I think Gen Z is incredibly sophisticated and intelligent and probably has had the most access to information that any generation has had,” says Stenberg. “It’s also important to laugh at the parts of ourselves that are flawed and hurting and strange, especially because we have no previous conception for any time or culture like this.” And when it comes to scary movies that play upon real-world fears, the idea of confronting the capacity for evil in all of us, the potential we all have to cause immense harm to the people we care about—that’s the greatest horror of all.

Keely Weiss is a writer and filmmaker. She has lived in Los Angeles, New York, and Virginia and has a cat named after Perry Mason.