I don’t recall when they first appeared, only that one day they didn’t seem to exist and the next they were everywhere. I spotted them—glittering, candy-colored pendants—first adorning the necks of my younger cousins, who were in high school at the time. They tapped their Elisa necklaces with absent fingertips, and when they laughed, their ears jingled with the glinting heft of the Danielle earrings. I’m not sure if I ever asked my cousins about the brand, but it didn’t matter: By the time my mother presented me with a gift from Kendra Scott, it seemed every girl in my Missouri college town already knew the name—and wanted to get their hands on that instantly identifiable box.

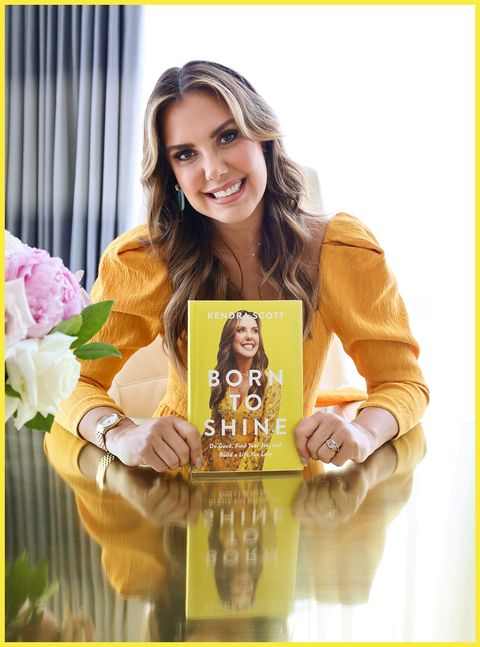

If within the past few years you’ve set foot in a Midwestern boutique, a Southern university football game, a local charity fundraiser, or your mother’s closet, chances are you know the color of that box. Not gold, not green, not quite chartreuse, but not a true butter yellow either. Kendra Scott, the founder and name behind the brand, writes in her recent memoir-cum-self-help book Born to Shine that the color is PMS 605C—though she just calls it “yellow,” as she does every shade of the hue that rules her wardrobe and her life. Even after stepping down as CEO in February 2021 for a more big-picture role as founder, executive chairwoman, and chief creative officer, Scott (and her sunny disposition) are impossible to extract from the brand whose fans lovingly refer to their jewelry pieces as their “Kendra.” Over the past two years, sorority hopefuls on the viral #rushtok TikTok hashtag, in particular, have made “Kendra” almost as common an utterance as “bid day.”

Scott and her now-20-year-old brand shattered the rules of the jewelry business, reversing the order in which most trends saturate the market. Kendra Scott exploded first throughout what is somewhat paternalistically known as Middle America before then spilling into coastal markets, in part on the wings of social media platforms. The company has acquired a following less cult-like than church-like, its followers attracted as much by the company’s extensive philanthropic efforts as by its affordable earrings. Every person I spoke to for this story, whether an employee, reseller, or customer, spoke of this “do-good” mentality with genuine reverence, an appreciation that bordered on awe. But 20 years is a long time in the eyes of the internet, and Kendra Scott is still a business—one that’s testing new waters as it assesses its next era.

In September, at the Spring Street Kendra Scott store in New York City—nestled (dare I say) triumphantly amongst a Chanel, Valentino, Cos, Longchamp, and Burberry—Scott met me for a glass of champagne beside the store’s Color Bar, one of the brand’s foremost success stories. (Similar to Nike By You and other personalization services, it’s where customers can customize jewelry.) Although buffed by her houndstooth jacket and gleaming white heels, the 48-year-old Scott exuded a Midwestern exuberance I recognized; though Austin-based, she’s originally from Kenosha, Wisconsin, and proudly a “coal miner’s granddaughter.” She’s what her customers might unironically refer to as “classy.”

I ask what business looks like now that she’s stepped away from the CEO job, and her face animates on cue. “I’m busier now than I’ve ever been,” she says. “I’m more excited and invigorated than I feel like I’ve been in so long, because I see where we’re headed. And it’s so exciting. I feel like I’m back in the days of the early startup, because there’s just so much that we want to accomplish.”

That renewed sense of urgency has, since 2016, beget new fine, demi-fine, and sterling jewelry lines; 2022 collaborations with brands including Summersalt and Barbie; the start of Scott’s television career as a Shark Tank guest judge; the launch of her personal Instagram account, further announcing her as a global personality; and even a men’s collection of timepieces, necklaces, and bracelets under the label Scott Bros. by Kendra Scott.

Outreach continues to expand as well. In 2018, the brand introduced college ambassadors known as Kendra Scott Gems, who are gifted jewelry in exchange for marketing on campus. A new direct sales program, started in 2022, allows so-called “community stylists” to sell jewelry for a commission. These moves speak to a larger top-to-bottom effort to keep Kendra Scott in the cultural conversation. The question is not necessarily whether the brand will survive into the coming years, but if and how it will inspire the same fervor in its customer base over time. So far, Kendra Scott seems to have little trouble attracting Gen Z attention, particularly amongst sorority members. Alpha Gamma Delta member Aubrey Gray, a University of Alabama freshman whose #bamarush videos racked up hundreds of thousands of views this summer, says she has no intentions of abandoning her Kendra for micro-trends—largely because it actually means something to her.

“Normally I wear Kendra Scott every day,” she says. “Everything I wore during Rush had a meaning.” She wore a bracelet she’d bought during a Kendra Scott fundraiser for her close friend, who was recovering from a severe boating accident; she wore a necklace from a different fundraiser for a child she used to babysit. And she wore the Kendra Scott Calvin ring, because “my boyfriend’s name is Calvin, so I got that ring to have with me during Rush, because he hadn’t moved into ’Bama yet,” Gray says. “Everything I wore had a meaning and was personal to me. And Kendra made that happen.”

Scott’s first retail business was similarly meaningful in approach, if a tad more myopic in execution. In 1995, at the age of 19, she dropped out of college and founded a hat company with the $20,000 her father had saved to send her to school. Her beloved stepfather, Rob, was dealing with brain cancer, and she longed to design the perfect fit for his sensitive scalp, and donate excess profits to cancer research. But merely stitching a cotton-lined cap was never going to be enough for Scott, who had long shared the fashion-forward tastes of her Aunt Jo Ann, a department store fashion director. Scott envisioned a renewed American wardrobe where hats were once again a staple accessory, as common as they’d been in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Hat Box opened in Austin, in what Scott writes in Born to Shine was “the worst mall in town,” where the store walls were covered in plywood shelving that Scott and her mother installed themselves. Customers trickled in, most perplexed by Scott’s assortment of fashion hats rather than baseball caps or beanies. Without steady profits, Scott’s philanthropic efforts were meager, even if well-intentioned. She writes in Born to Shine, “We’d been able to write a few small checks toward cancer research, but it didn’t seem like enough when Rob was disintegrating in front of us.”

In 1998, Rob passed away, leaving Scott with the wisdom she says still guides her to this day: “You. Do. Good.” At the time, those words didn’t inspire much comfort. The Hat Box wasn’t working. Rob was gone, her peers were either in school or had already graduated, and she was running a failing business with no college degree.

“What was funny is, I was making jewelry in my hat store,” Scott tells me now. “And it would sell out the day I put it by the cash register. My future was right in front of me, but I was too blind.” Five years after opening The Hat Box, she closed its doors forever.

By the early 2000s, Scott had married, left her job working in ad sales for a travel company, and launched a small branding and marketing business called Glitter Public Relations. (Forgive her, she implores—again, it was the early 2000s.) In 2001, she found out she was pregnant with her first son, Cade, and she filled the spare hours with jewelry classes, perfecting a skill she’d already been honing as a hobby for years. She met future customers in Mommy and Me classes, where she’d remove the homemade pieces on her neck and ears and give them away, if someone happened to express interest. Scott had already noticed the gap in the jewelry market simply by being a customer herself: When she shopped, she yearned for bold colors, high-quality metals, and semi-precious stones, but the $200+ price tag made her balk.

The Kendra Scott brand filled this space. It materialized first in 2002 as Kendra Scott Jewelry, then Kendra Scott Designs, a tiny operation out of Scott’s spare bedroom that was 100 percent wholesale. Scott strapped her son into a BabyBjörn and took him cruising around Austin, earning enough orders at boutiques and department stores for product to begin overflowing out into the rest of her house. By 2005, the company was already outgrowing a small attic office on Austin’s West 6th Street, where friends and co-workers Leah Lucus, Denise Chumlea, Cheryl Mills Knight, and Sarah Ott were members of the so-called “Super Seven,” the little crew that spurred Kendra Scott’s early success. All four are still with the brand to this day.

Says Chumlea, now Vice President of Design at Kendra Scott, “You could tell, this woman…she had grand plans, and she just had this magnetic quality to her that you wanted to ride the wave with her.”

This time, the wave kept going—and growing. In 2006, Kendra Scott moved to a Penn Field space on South Congress Avenue, and narrowly survived the 2007-2008 financial crash thanks, in part, to a sizable order from Nordstrom. Scott also took what, in hindsight, was a nearly inconceivable leap of faith: After a divorce and in the midst of a recession, she switched Kendra Scott’s business model from wholesale to direct-to-consumer, opening up customer orders on the brand’s website.

At the same time, she launched what might be the singular development most responsible for the brand’s early explosive success: The Color Bar. At Henri Bendel’s, the company hosted its first design-your-own-jewelry experience, where shoppers could pick the stone cuts and colors they wanted and watch the pieces get assembled before their eyes. Shoppers lined up down the block, and the model stuck. The Color Bar is now a fixture at Kendra Scott stores across the country, as well as online. By 2010, Kendra Scott opened its first brick-and-mortar flagship shop on South Congress, another risky business choice given the economy’s sluggishness.

But the brand had found its message, and it was one that thousands of women wanted to hear. You could be loud. You could be colorful. You could be unique, and you didn’t have to pay much money to look it. The Kendra Scott price point generally fell between cheap costume jewelry and the demi-fine category, meaning many products were good-quality but below the $200 mark. And, in Texas, where college football and sorority culture were as essential as good barbecue, “wearing your colors” was a daily ritual. Kendra Scott’s Color Bar allowed Alpha Chi Omegas and Alpha Delta Pis, Aggies and Longhorns fans alike to design pieces with their group colors, aligning them with their subcultures in a trendy, approachable manner. The Danielle earrings first racked up sales in 2008, before the Elisa necklace overtook its record in 2015. Both are now iconic Kendra Scott bestsellers, particularly amongst the college crowd, who influenced their mothers and younger sisters to start shopping.

When they love something, “Southerners scream it from the rooftops,” Scott says. “And they tell everybody they know. They really will. And I didn’t have a marketing budget; I didn’t have that flexibility. I started with $500. I was a single mom, but I had the voice of Texas literally helping me propel my brand. And I think it has worked.” Before long—in the South, at least—the Kendra Scott name was evoked with the reverence of religion.

Today, Kendra Scott is an enormous enterprise, with 130 stores across the U.S., an estimated $360 million in annual sales, and a valuation that sits above $1 billion, according to The Wall Street Journal. And the brand is arcing through a fascinating turning point under new CEO Tom Nolan, who took over in 2021 and helped guide the 2022 launch of engagement rings and watches. The company retains the Kendra Scott name, and Scott is as involved as ever, though her activities these days are more creative and philanthropic. (A Kendra Scott spokesperson cites the founder’s current focuses as “design, customer experience, product expansion, and philanthropy.”)

“When she stepped down as CEO, one of the big reasons was for her to really continue to get further involved in philanthropy,” says Sheena Wilde, Vice President of Philanthropy and Belonging at Kendra Scott. “You have to remember, when Kendra started this business 20 years ago, she was already figuring out how to support people even when the company wasn’t financially making any money.”

But there’s more than enough money to go around now. Since 2010, Kendra Scott has donated more than $50 million to primarily women’s and children’s charities, thanks in part to thousands of so-called Kendra Gives Back events, where local groups can host shopping sessions in which 20 percent of Kendra Scott proceeds go to their charity of choice. Wilde also helps handle corporate giving, which focuses on partnering with other organizations and doling out grants, as well as launching collections that have benefited groups including the Breast Cancer Research Foundation; Hurricane Ian disaster relief; and Ubuntu Life, which supports children with special needs in Kenya, to name a few.

“I look at our Give Back number as much as I look at my top-line revenue,” Scott says. “It’s in my dashboard I get as chairwoman. I want to see that. I want to see that we’re hitting those numbers, that we’re making sure that we’re doing the right outreach.”

While many feel deeply indebted to Kendra Gives Back events—including #rushtok user Gray—some shoppers have criticized the approach as profits-driven, given that the donations come about through sales of Kendra Scott jewelry. Wilde says that the company has historically used these shopping events for much of its philanthropic efforts, yes, “but our corporate giving…is fairly there as well, in comparison to what we’re driving from the community level, too,” she says.

A Kendra Scott spokesperson reiterated this, adding, “Our Community Giving is driven by Kendra Gives Back events, while Corporate Giving is driven by planned and responsive grant giving and national partnerships. The amount we give continues to grow as the company scales.”

Multi-level marketing critics have volleyed similar criticisms at Kendra Scott following the launch of the company’s direct sales program in March 2022, which employs stylists as 1099 contractors to sell jewelry in communities where Kendra Scott does not have a strong retail presence. (Other well-known direct sales businesses include LuLaRoe and Mary Kay, the latter of which Scott’s mother worked for during Scott’s childhood.) After a social media firestorm following the program’s announcement, the brand has continually insisted Direct Retail by Kendra Scott is not a multi-level marketing scheme, in part because it does not require stylists to participate in recruitment efforts. In response to a request for clarification, a Kendra Scott spokesperson stated that Direct Retail by Kendra Scott is meant to “empower female entrepreneurs” as “another vertical in our omnichannel retail model.” They added, “Building teams, recruiting others, and holding inventory is not a component of our program.”

Apart from the philanthropy growth and new business initiatives, Kendra Scott is also shifting its product to reflect an evolving customer base. Scott recognizes that it’s not 2010 anymore, even given the resurgence of Y2K fashion; in fact, some of the most successful designs, such as the Elle, Danielle, and Elisa, are so ubiquitous that trend-savvy customers might outright avoid them. (The spokesperson shared that, even now, Kendra Scott sells an Elisa necklace every minute.) My own mother attended a Kendra Gives Back event just a few weeks ago, and found it “refreshing” that she could easily dodge Elisa pendants while shopping for a friend whose taste is more “unique” and “mature.” The new collections with Barbie and Texas influencer Emily Travis; the engagement rings and Scott Bros. watches; the demi-fine stacking rings and huggie earrings—they all speak to the brand’s embrace of a new future that is still characteristically Kendra Scott.

But don’t call these moves a pivot. “I would say it’s more of an expansion,” Chumlea says. “We still want to remain approachable and have that same attainable luxury.”

Expansion alone can’t pave over the common perception that most of the shoppers are “upper middle class white conservative christian ladies lol,” as one Reddit commenter plainly put it earlier this year. And particularly on southern campuses, Greek organizations have come under fire for their homogeneity and long-running associations with racism and sexism, leading to skepticism by association for Kendra Scott. Scott disagrees with this assessment. She believes that’s only “one aspect of our customer base,” she says. “I get to see, every day, our customers. I get to see our store employees. They’re unbelievably diverse. You can walk into any of our stores and see that. And I think with Scott Bros. launching, with unbelievable success, we have a very diverse customer base.”

The Kendra Scott spokesperson declined to share internal diversity, equity, and inclusion data with ELLE.com. Instead, they provided the following statement: “Since its inception, Kendra Scott has been committed to uplifting our community and our team of diverse employees who represent a variety of aspects of diversity including but not limited to race, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic, sexual orientation, and generational diversity. We proactively promote difference as a strength and embody this in our core values consistently. Diversity isn’t a program nor a one-time notion at Kendra Scott. It is a daily, intentional, and ongoing practice.” A cursory scroll through the company’s Instagram speaks to this effort.

Twenty years on, Kendra Scott is still doing big business. Amy DeSalme, owner of the boutique Avery & Abby in Chesterfield, Missouri, says she stocks her wholesale Kendra Scott products “front and center” at her store, which pulls in women of all generations: preteens, college students, retired grandmothers, and women in their 30s like her. These women “want nice things, but we don’t want to necessarily spend a ton on ourselves,” she says. “We’re just not going to do it. But we also don’t want junk. We want something that’s going to last. We want something that we can wear over and over.” With Kendra, “There’s this mass appeal. I’m actually going to be expanding my Kendra section because it does so well for me. It does so well for me.”

Away from her former CEO role, Scott herself still drives many of the brand’s big decisions: She remains the object of devotion for her employees and customers. They want to support her; they want to be her. What many might deride as her “girlboss” attitude, others embrace for its passion and earnestness, wrapped in non-threatening Midwestern-meets-Southern packaging. Director of Customer Care Lyndsay Baylor, whom a Kendra Scott spokesperson said was only available for an email interview, put it like this: “The word ‘light’ comes to my mind when I think of the first time that I met Kendra Scott. She is so warm, inviting and was truly glowing. I have always wanted to work for her because I connected with her story as a woman in business and as a mother. Each time that I have met her, it is reaffirmed that the decision I made was the right one.”

But Scott’s success is thanks to her quick thinking as much as her tender sensibility. When the Alabama #rushtok hashtag first took off in 2021, Scott immediately saw the opportunity the sudden spike in Kendra Scott customers had revealed. Suburban mothers might be a core Kendra Scott base, it’s true, but so are their daughters and their daughters’ friends—especially those posting their outfits on social media. And whom better to influence their mothers, friends, and family—plus those outside their own demographics—than young women? As #rushtok continued into 2022, Kendra Scott sent products to TikTokers as a thank-you gift and engaged with their videos across social platforms. The organic strategy worked: The Kendra Scott name spilled outside the sorority bubble and into other corners of the internet, attracting new and old devotees alike.

DeSalme was one of those influenced. “My best girl friend, she is 32 years old, and she’s a new mom, and she was very into following the #bamarush [hashtag] on TikTok,” she says. “In fact, we joked about it so much. She’s like, Well, I got to see what the ‘Bama girls are doing so I know what to wear!” Sure enough, she recognized the baubles bouncing on their necks: a great reminder to order her next Kendra Scott restock. When she speaks of the brand now, DeSalme sounds almost giddy. The product offerings are expanding; her sales are picking up. The church of Kendra Scott is keeping her fed.

Associate Editor

Lauren Puckett-Pope is an associate editor at ELLE, where she covers film, TV, books and fashion.