Content warning: The following story contains mentions of suicide.

There are so many aspects of health that disproportionately affect the Black community, and yet less than six percent of US doctors are Black — a deficit that only further harms public health. Many of the Black folks who work in healthcare have dedicated their careers to combatting inequities. That’s why, this Black History Month, PS is crowning our Black Health Heroes: physicians, sexologists, doulas, and more who are advocating for the Black community in their respective fields. Meet them all here.

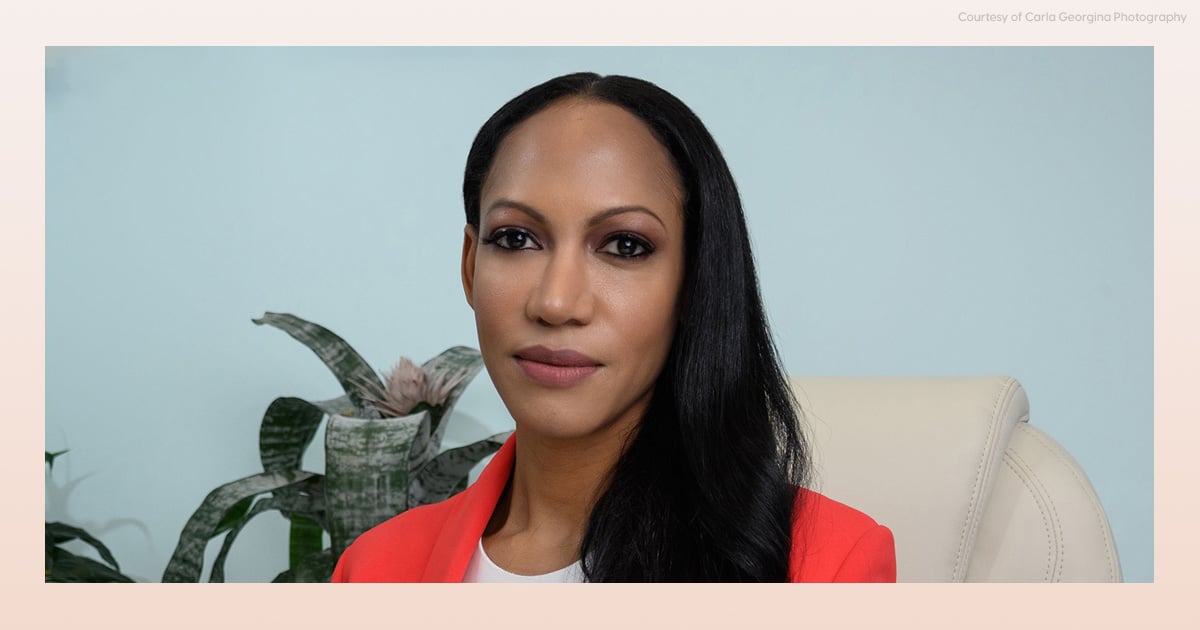

You may have scrolled across psychiatrist Judith Joseph, MD, on TikTok or Instagram. Her videos educate people on the reality of mental health conditions and issues, including high-functioning depression and attachment styles. But although her follower counts are in the mid-six figures and she posts near-daily, that isn’t close to the majority of her job.

Dr. Judith is a practicing psychiatrist at New York University Langone Health, chairs the Women in Medicine Collaborative at Columbia University, and has a research lab that recently helped develop the first FDA-approved medication for postpartum depression. Plus, she works out every day and reads one to three books a week. (What version of 75 Hard is that?)

We asked Dr. Judith about how she got into the mental health field, her pathway to becoming a social media personality, and why being a Black psychiatrist is so important to her in a field that’s traditionally failed Black communities.

PS: How did you first become interested in psychiatry and high-functioning depression?

Dr. Judith: When I first matched in a residency, it was in anesthesiology at Columbia. But then something happened in my fourth year of medical school: I ended up getting a grant to go to South Africa with some of my peers to work in an orphanage for children who were either HIV-infected or whose parents had died of AIDS.

We were there for about a month and we did these trauma-focused groups helping the students deal with and address their trauma from losing a loved one, from feeling abandoned, from all the atrocities that they had witnessed. And that really stuck with me.

When I got back, as I was doing my anesthesiology rotations, I didn’t really feel satisfied. Anesthesiology is a competitive field to get into. My parents were proud because I was the first doctor in the family — the first college graduate in the family. But it didn’t really feel like the work was feeding my soul. I know it sounds cheesy.

But you know, a lot of doctors walk around, not really unpacking their trauma from medical school and residency. We see a lot of death, and the unwritten code is that you’re not supposed to talk about it; it’s part of the job. But you see high rates of depression and substance abuse in doctors, especially in surgical fields, because there’s a lot of unprocessed pain. So I started being interested in how people in medical fields process their trauma — because I was not processing my trauma.

When I was two years into my anesthesiology residency, I got very real and honest with myself and said, “I don’t like this and I don’t think I can do this anymore.”

I had friends who were in psychiatry telling me how psychiatry was a really good field. And I remembered how gratifying the experience in South Africa was for me. There was an opening at Columbia at the time and I applied for it and got chosen to be a psychiatry resident — and I never looked back. I love the field of mental health.

Now, I come from a Caribbean family that’s very traditional. So mental health, in my family at least, was talked about in terms of spirituality. Conditions like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were seen as — oh, that’s spirits or something. So when I told my family I was considering psychiatry, they were like, “That’s not a real doctor. Why are you going to leave a prestigious field to work with crazy people?”

It took a lot of education within my community to explain that mental health conditions are part of the body because the mind is part of the body.

PS: Why is it important for you, as a Black doctor, to be working in mental health practice and research?

JJ: The people who are the fathers and the forefathers of psychiatry were not diverse. During training, I was the only Black resident in my class. But a lot of mental health conditions are expressed differently in minority populations, and we need to address how we approach [conditions like] depression across the board in a diverse way.

So there’s a real need for diverse psychiatrists. There’s a lot of misinformation because doctors do not look like us, and studies show when you have representation in medicine and healthcare, you get better diagnoses.

“We went through slavery and racism — of course we have depression.”

There’s a lot of misinformation within the Black community. For example, for many years, it was thought, “Oh, Black people are just so happy. They don’t have depression.” Are you kidding me? We went through slavery and racism — of course we have depression. But we may not show it the way that you’re used to seeing depression depicted in the movies. Black people express it differently; they may come across as irritable, as angry. It’s expressed differently in different communities.

[Recently, we’ve been seeing that] one of the highest rising rates of suicide is in adolescent Black girls. And this was a group that, in the past, studies would say, this is a protected group. Well, those studies were wrong.

One more [example] is that many times Black kids, especially Black boys, will be diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder or [similar] conditions. But a lot of these children actually have a history of ADHD and some have a history of trauma. So again, there are disparities in medicine where conditions are painted bad for Black kids. I do a lot of education for parents about this.

PS: Your social media accounts have huge followings. How did you first get into social media content creation?

JJ: My interest in social media stems from seeing patients in my practice over the pandemic who are glued to their social media and self-diagnosing.

One of the things that I was coming across is people were being referred to me for ADHD medication and they didn’t have ADHD. So I saw that people were being incorrectly diagnosed with conditions because they were at home, tied to social media during the pandemic, because that was a lot of their source of soothing — being online. So I felt that there was a responsibility for me as a physician who teaches medical media to then practice what I preach, right?

Not that there’s anything wrong with someone who has a condition advocating — that’s great, it decreases stigma. But just because you have your one experience, which is anecdotal, doesn’t mean you can apply it to millions of people.

I decided it was my responsibility to start posting videos, around February 2022. My account grew within less than two years. So there’s clearly a need for good information.

But there’s just not enough people out there willing to do it. A lot of doctors are afraid of getting sued, and also they don’t want to look grandiose and they just don’t have the time. It’s risky to put yourself out there on social media. Just by stating facts — like that there’s systemic bias in medicine — you can get canceled. But we have to do it. If we don’t put the information out there, then people don’t know it and change can’t happen.

I also have a newsletter and podcast, [“The Vault With Dr. Judith”]. There’s so much you can’t say on social media — things like “suicide.” But suicide rates are rising in Black communities. You also can’t talk about sexual health on social media. So I like to direct people to my newsletter and podcast, where there’s more freedom to talk about things.

PS: You’re open about how hard healthcare work is on mental health. Given your line of work, how do you care for your own mental health?

JJ: Many therapists go into their office and it’s just them, right? But I’m fortunate in that I have a team of people that I work with and I just could not do it without them. Because I’ve been intentional in the way that I organize my schedule and my businesses, I have time to take care of myself.

I work out every day. It may not be an intense workout because that’s not good for your body to do it daily, but it’s some form of movement.

Also, I was a neuroscience undergraduate researcher and major. So I’m a strong believer in nutritional psychiatry, and eating to feed the brain cells. Over the years, I’ve been really intentional in what I put into my body because I know that that does support brain functioning, mood, and sleep.

“We may not all have a mental health condition, but we all have mental health.”

I think a part of why my social media hits is because like I’m a lifelong learner, I love learning. I’ll read like one to three books a week, and every time I learn something new, I try and condense it into a one minute reel to teach my followers, so that they’re going back to school with me.

Finally, the moment you start in psychiatry training, they’re like, “OK, here’s a list of doctors, we’ll subsidize your therapy. We heavily encourage you to be in therapy.” And it’s like, thank God for that. Before I entered my therapy when I was a resident, I thought, I don’t have any problems. Then learning about child development and the way that you’re raised and attachment theory, I was like, holy crap — I have issues, too.

You know, we may not all have a mental health condition, but we all have mental health. And just like with physical health, we have to maintain it, and a huge part about maintaining your mental health is understanding it and educating yourself about it. The more informed you are about your mental health history and your psychological development, the better your providers can support you.

Image Source: Carla Georgina