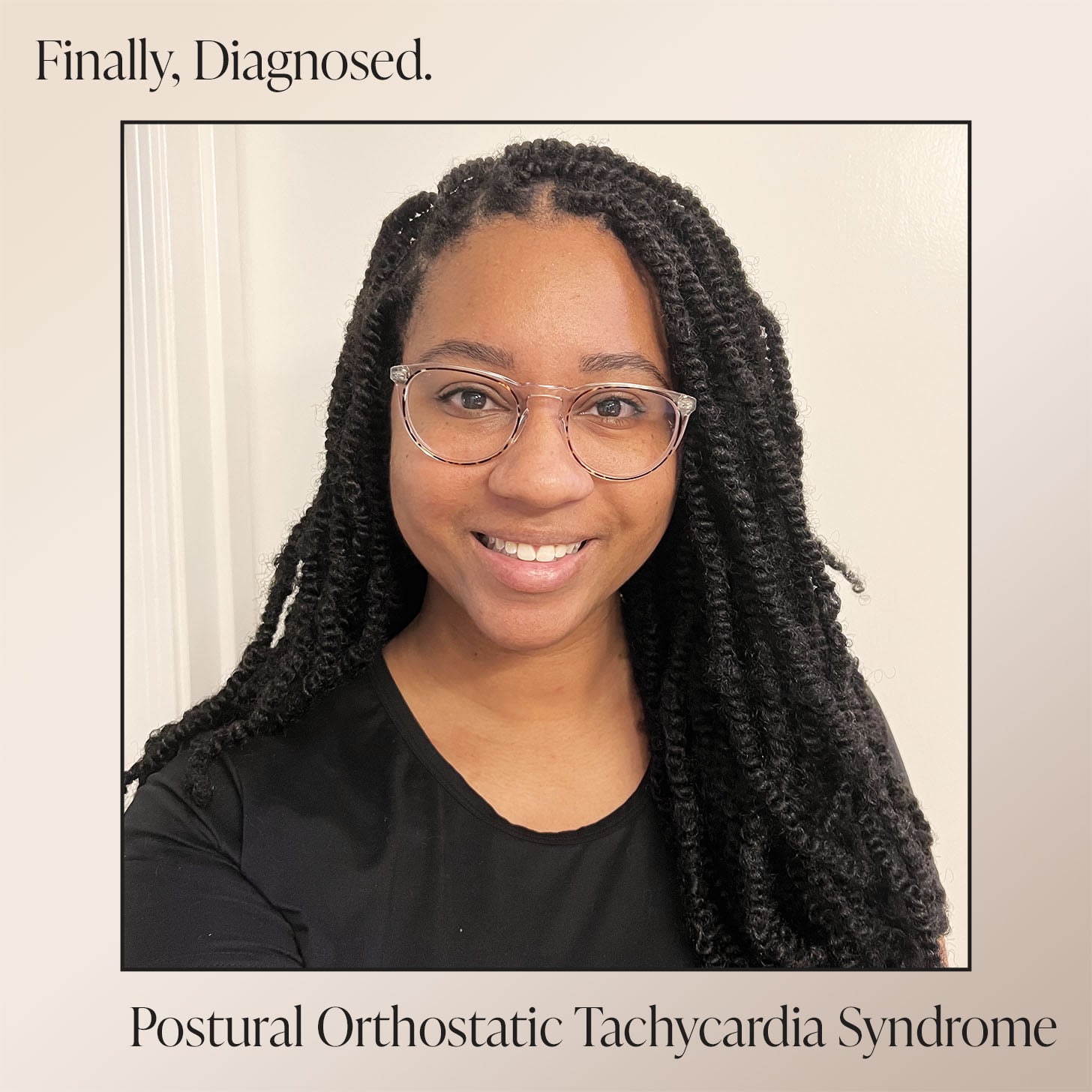

Grace Bundy, 28, has a unique relationship with the floor. Growing up naturally tall and bendy (which she would later learn at 19 was a manifestation of Ehler’s Danlos syndrome), her parents enrolled her in competitive gymnastics. She spent countless hours bending her body to the floor’s demands in order to defy gravity and land impressive tricks. But at 13, her relationship with the floor changed. “I just started having these issues with fainting upon standing,” she tells POPSUGAR. “Being a gymnast, not being able to stand — it’s kind of an issue.”

When Grace’s parents took her to get checked out by a doctor, she was diagnosed with vasovagal syncope, which is essentially fainting caused by certain triggers like seeing blood or experiencing emotional distress. “They kind of just told me to clench your core and bear down if you feel like you’re gonna faint,” she says. Grace spent the next seven years dealing with unexplainable fainting, seizures (which she would later learn was epilepsy), and symptoms of Ehler’s Danlos syndrome, including extreme hypermobility to the point of injury.

It wasn’t until Grace went to college that she was unknowingly treated for POTS.

During her sophomore year of college, Grace went to see a university physician because her fainting had become more frequent. “They gave me salt tablets and they made me really ill. So they took me off those and they put me on what I now know were beta blockers,” Grace says. “But at the time, they just told me it would help my fainting.”

@labelleddisabledgrace Some facts about POTS #chronicillness #pots #potssyndrome #potsawareness #aintitfun #paramore #fyp #trending #viral

Years later, Grace would do her own research and learn about POTS, short for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a group of disorders that can cause fainting due to sudden, reduced blood volume and increased heart rate upon upon standing up, per Cleveland Clinic. She would also learn that POTS can be treated by medications used to increase salt retention and blood volume, in addition to beta blockers which can treat tachycardia, or irregular, rapid heart beat.

In 2020, Grace went to see a cardiologist and asked them about POTS and whether or not the doctor thought she might have it. “She said, ‘Yes, of course you do, it’s in your charts,’ which was shocking to me because it feels like something I should have known,” Grace says. “I just didn’t ever remember hearing the term POTS, I just remember them saying, ‘These will help you with fainting.'”

Grace would also learn that POTS wasn’t the only condition that’d been causing her to pass out. The seizures she’d been experiencing from time to time were actually a form of epilepsy.

Looking back now, Grace says that she’s had symptoms of mild seizures since she was a kid. But they were often just brushed off, given her history of fainting. It wasn’t until college when the seizures, along with her fainting, became more pronounced and she went to see a neurologist. He performed an electroencephalogram (EEG) to check for abnormalities in the brain, but Grace was ultimately told that it wasn’t uncommon for girls her age to have seizures and that it would probably go away.

“When you know something is wrong, you know something is wrong.”

The only recommendation the doctor gave her was to get a service dog. “So I got a seizure training service dog and she was great. She learned all my seizures,” Grace says. And of course, she was helpful for fainting, too. But it didn’t lessen her the frequency of Grace’s seizures. In 2020, before Grace learned of her POTS diagnosis, she was fainting every day, multiple times a day, and having seizures about eight times a week. It wasn’t until she went to see a neurologist for migraines and told them about her seizures and fainting that she was recommended to a seizure neurologist. “She did a two-hour EEG and came back and said, ‘You have epilepsy, it’s clear on your results and you need to be medicated.'”

Grace’s reaction to it all? “I remember being mad first,” she tells POPSUGAR. She found herself particularly angry at the doctors she saw in college who didn’t take her symptoms of POTS or epilepsy seriously. But eventually, that anger turned into relief, she says. Ultimately, having these diagnoses meant that she could “find other people who have the same thing” and better “navigate life, now that I know what’s going on.”

Today, Grace manages her conditions with a series of treatments and a whole lot of resilience.

For Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Grace has a variety of pain management methods that she can employ, from ice and braces all the way up to opioid medications for severe flare-ups. For POTS, which was exacerbated by getting COVID and after giving birth to her son, she gets infusions three times a week through a port in her chest to replace the blood volume that she doesn’t have. “And then epilepsy is the easiest,” Grace says. “I just take medication in the morning and in the afternoon.”

It addition to the medications, it’s also managing the reality that “sometimes I can’t go do something or sometimes I can’t stay out as long as I might want to because I’m overdoing it,” Grace says. She’s learned when to push herself and when to rest. She’s also learned that listening to your own body is crucial when it comes to taking care of her health. This is especially true as a woman and even more so as a woman of color. “When you know something is wrong, you know something is wrong,” Grace says. Her advice to others when it comes to making doctors listen? “Document, document, document.”

“If you can film a symptom happening, that’s major. If you can write down all of your symptoms from the time up to your appointment, so that you can bring in a list of ‘this is what’s happening, and it’s happening to me every single day’ — I find that they listen a lot better when you have it in front of you,” Grace says.

And one of the most valuable lessons she’s learned from her entire experence: “It’s totally okay to say ‘I think that this is not the doctor for me,’ even if it’s just because they’re not listening to you.”

Each year in the US, an estimated 12 million adults who receive outpatient care are misdiagnosed, and oftentimes, those patients fall within a minority identity, including women, nonwhite Americans, and those within the LGBTQ+ community. That’s why we created Finally, Diagnosed: a monthly series dedicated to highlighting the stories of those who’ve been overlooked by their doctors and forced to take their health into their own hands in order to get the care they deserve.

Image Source: Grace Bundy/Photo Illustration by Ava Cruz