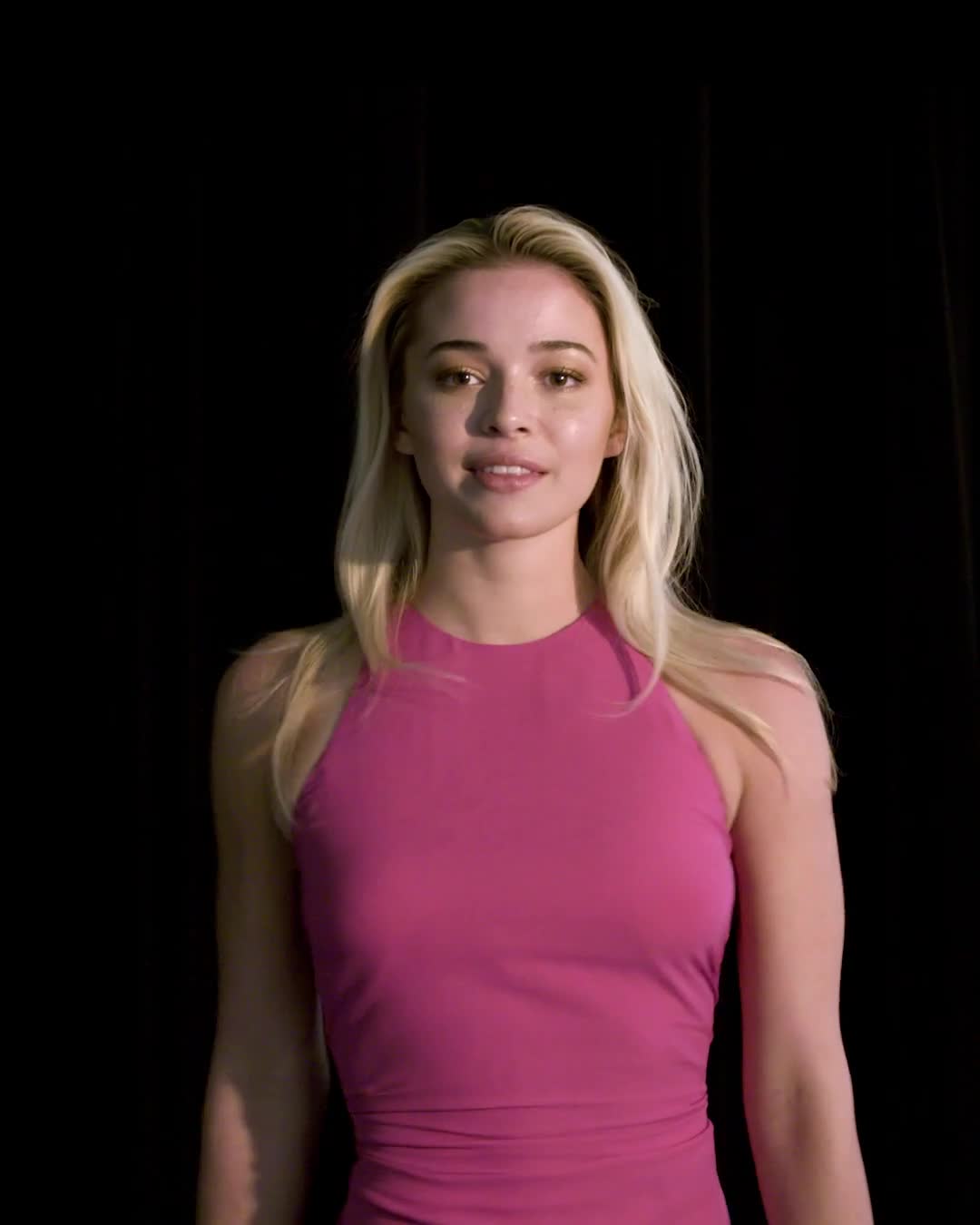

On July 1, 2021, Louisiana State University gymnastics star Olivia Dunne was in Times Square staring up at a 73-foot-tall version of herself. A video clip that played on the billboard showed the most-followed athlete in college sports starting a flip on a beach on TikTok and transitioned to her sticking a landing in her LSU uniform in the school’s arena, her arms lifted triumphantly overhead.

The campaign, which was paid for by LSU and spotlighted other athletes as well, was a victory lap following the NCAA’s decision to overturn its 115-year prohibition on student athletes earning money for their name, image, and likeness (NIL). “That was the moment my life changed forever,” Olivia tells me as she sips a drink outside a campus Starbucks on a sunny spring day in Baton Rouge.

LSU had taken fourth place at the national championships the weekend before, an impressive showing given the number of injuries the team suffered this season, and she was enjoying a rare moment of downtime, dressed casually in black leggings and a cropped T-shirt, her long blonde hair spilling over her shoulders. If not for the Prada bag slung on the chair behind her, she’d be indistinguishable from the other students passing by. Pausing to reflect on that Times Square moment, she adds, “That was surreal. I didn’t really know what was to come, but I knew it was going to be special.”

Two years later, Olivia is still the most-followed college athlete in the country, with more than 13 million followers across platforms (7 million-plus on TikTok, 4 million-plus on Instagram, 1 million-plus on Snapchat, and 87,000-plus on Twitter). She’s turned all those eyeballs into cash, netting millions per year in endorsement deals. Olivia currently ranks second to USC men’s basketball commit Bronny James on On3’s NIL 100 List of top high school and college annual-earning projections, and one ahead of Texas quarterback Arch Manning. The obsession with her runs so deep that you can buy a throw blanket with her face on it for $61.45, while T-shirts that read “Mentally Dating Olivia Dunne” go for $23.34.

Every time she posts, within seconds the comments roll in: “wow,” “so pretty,” “love you,” “marry me,” “mommy.” And inevitably some version of: “Is this appropriate?”

With all the attention and all the zeros in her bank account has come a dark side of fame, one that women college athletes are more vulnerable to than their male counterparts. There are the trash websites that follow her every move, oversexualizing even the most innocent of her posts. (When she posts a selfie in a white crop top, she’s putting on a “busty display”; a beige top “causes a commotion.”) The headline that says “sex sells,” atop a story on women athletes and NIL that focuses on her looks and discounts the skills and years of hard work it took for her to amass such a large audience. (There are plenty of beautiful blonde women in college gymnastics; Olivia is the only one with 13 million-plus followers.) And then there are the people who blame her when her testosterone-crazed male fans get out of line, as they did at a meet at the University of Utah earlier this year.

“To see a woman winning? People sometimes have a lot to say,” Olivia says of her haters. She speculates that some of the criticism she faces may simply be the product of her being the first woman to do A Thing. “If you’re a woman at the forefront of something, when you’ve got eyes on you, people are going to downplay your success and say that you’re not doing it right, that you don’t deserve all the opportunities,” she says. “I don’t want to say ‘F you,’ but the best way to get that to stop is to keep being successful at what you’re doing, because your success, and love for what you do, will outshine any of that.”

As Olivia navigates all of this as arguably the first millionaire college influencer/athlete—or is she the first millionaire college athlete/influencer?—one thing is certain: The incredible story of Olivia “Livvy” Dunne proves college sports will never be the same again.

Long before she was @livvy, Olivia was a three-year-old growing up in a ranch-style house in suburban Hillsdale, New Jersey, with her eyes on a prize: a sparkly pink leotard, just like her cousin’s. “I was like, ‘Mom, I want that,’ and she said, ‘Well, you can’t have a leotard unless you do gymnastics,’” Olivia explains. “So I was like, ‘Sign me up.’”

It turned out she was a natural. “I remember being quite strong for a three-year-old,” Olivia says, recalling how her coach would put her on the rings, a men’s apparatus, and she could hold herself up with ease while being swung back and forth, which, she says, “I can barely even think about doing right now at 20 years old.”

Olivia started competing at age seven, once moving up an incredible four levels in one year. By the time she was 10 years old in 2013, she had reached level 10—the highest level before elite. With her sights set on the Olympics, she started attending national team training camps, then left public school in seventh grade to homeschool with her mother. When LSU began recruiting her (rules about how soon schools could reach out were looser then), she had a very 12-year-old response to the university’s efforts. “I liked LSU at first because one of their colors was purple,” Olivia says, laughing. “I was a baby.”

When she was just nine years old, she joined the year-and-a-half-old platform Instagram. One thing many people don’t realize about Olivia—especially those who like to say she’s “turned the male gaze into a gymnastics empire” (as one recent headline in the Guardian read)—is that she is not an overnight sensation. She’s been building a brand and amassing an audience on social media for more than half her life. And the gymnastics part came first.

“I remember, I got my first professional pictures on a podium and I was like, ‘OMG these are awesome! I want more of this in my life!’” Olivia says. She posted them on Instagram and watched the likes roll in. “I just knew this is something I wanted to do,” she says. “I was 10 or 11, and there were younger girls looking up to me and people starting to recognize me. To be someone else’s role model meant the world to me.”

In those early days, Olivia still had her natural brunette hair color, and her feed was full of badly-lit selfies, pics of her meeting her gymnastics idols, and videos of her performing new moves. “Livvy was so cute with it,” says coach Jen Zappa of ENA Gymnastics in Paramus, New Jersey, where Olivia trained. “She would work so hard to master a skill, and then she would want to get the perfect version on camera.” Olivia and her friends, known as the “Chalk Girlies,” would post tutorials on the gym’s feed about what they were learning. She later drew a blue check in the corner of her bedroom mirror, manifesting her eventual verification on Instagram.

Olivia comes from a family well-positioned to raise a social media star. Her maternal grandmother founded an early education technology company called Imagine Tomorrow. Olivia’s parents, Kat and David Dunne, who met at Rutgers University (her dad attended on a Division 1 football scholarship, and her mom studied business and education), both went to work for Imagine Tomorrow after graduation, bringing tech into schools and opening computer centers for young children.

Consider Kat the Kris Jenner of the Livvy operation. “My kids all grew up with technology in their hands, and I’ve always been a big advocate of putting technology in the hands of kids and teaching them how to use it safely. If you’re going to have your phone in your hand, don’t just scroll through—let’s make content, let’s do something,” she says. “So many parents treat technology in the opposite way. They think of it as just, ‘You’re wasting your time.’ But if that’s what your child is interested in, then what can it become?”

Olivia made her elite debut at 11, and three years later, in 2017, she was officially named to the USA Gymnastics Junior National Team. The team went on to win the City of Jesolo Trophy in Italy, while she earned fifth and ninth places, respectively, in the individual all-around in the Juniors division at the U.S. Classic and National Championships. But being a member of the national team also meant training at the 2,000-acre Karolyi Ranch in rural Texas.

According to an independent investigation conducted by Ropes & Gray, the ranch, run by longtime coaches Bela and Martha Karolyi, was a punishing place in an isolated and secluded environment away from the gymnasts’ parents. “I remember the first time I went, I thought it was going to be a fun summer camp with gymnastics. No. I was completely wrong,” Olivia says. “It shut down, obviously, because it was not a good place. But I went from the age of 10 until I was 16—that was the only way to make your dreams come true as a gymnast.”

Describing the expectation of perfection and single-minded focus on training, she says, “It was honestly abusive there, but that was the only way.” (In a Dateline interview, the Karolyis admitted the atmosphere at the ranch was intense, but have denied any wrongdoing, including any claims of abuse or enabling abuse. USA Gymnastics severed ties with the ranch amid the allegations involving the ranch.)

As her mom tells it, Olivia was at a national team training camp “when literally all of USA Gymnastics basically fell apart” because of the Larry Nassar sexual abuse investigation. The program’s top leaders eventually stepped down or were fired; the ranch closed; Nassar was sentenced up to 235 years in prison for sexual assault at various facilities and clinics in Michigan and for child pornography offenses. “It was an emotional time for anyone who was in gymnastics—knowing people who were impacted personally, and knowing it could have been you too,” Kat says. “When so many people were affected, you knew that to not have it impact you was…you were just lucky.”

On top of all the turmoil at USA Gymnastics, Olivia had been dealing with an ankle injury. She faced a choice: Step back and focus on healing, or continue to train at the elite level. Through conversations with her family—including her aunt, Kat’s sister Laura St. John, a celebrity mindset coach in Malibu who has appeared on Netflix’s Selling Sunset—she began to see past her Olympics dream to a new path. In 2019, she signed a National Letter of Intent with LSU, which awarded her a full athletic scholarship.

Like the rest of us in the spring of 2020, Olivia found herself with a lot of time on her hands. Gyms, where she had spent about 30 hours a week, were closed; meets were canceled. In March, Olivia and her family were visiting Jensen Beach, Florida, where both sets of her grandparents now live, and “then the world shut down and we got stuck there,” Olivia says. “We were right on the beach, so I was like, ‘This could be worse.’”

She posted videos of herself doing flips on the sand on TikTok, calling it “beach-nastics.” They were a hit; she started gaining hundreds of thousands of followers a week. “I don’t know if it was just a little glimmer of positivity, but people loved the vibes in my videos,” Olivia says. “Being on the beach, being happy, smiling—a bit of sunshine during such a dark time in the world. I feel like, I don’t know, I used it to my benefit.”

Her mom says she brought an athletic-level intensity to her social media. “She was used to following a schedule, so she just started doing social media like it was her job,” Kat says. “She would sit down, make a schedule, map out what kinds of content she’d do, and then watch how it performed.” She enjoyed studying the analytics and algorithms, watching the likes-to-shares ratio, and seeing how her followers engaged with a post. NCAA eligibility rules at the time meant that, while Olivia could continue to grow her following as an LSU student athlete, she couldn’t monetize it. “She came to college with this audience, and for her not to be able to use her own name, image, and likeness because it was wrapped up in these NCAA rules—basically, they owned her—was really unfair,” Kat says. “She couldn’t earn a single dollar. The rules were so strict, she couldn’t even take a cup of coffee for free.”

In 2019–2020, an antitrust lawsuit brought by student-athletes challenging the NCAA’s restrictions on compensation was making its way through the courts. By June 2021, 19 states had passed fair-pay-to-play laws bucking the NCAA’s long-held belief that student athletes should not be paid for their name, image, and likeness. On June 21, in a 9-0 decision, the Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling that struck down caps on student athletes’ academic benefits. In a scathing concurring opinion, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh addressed the remaining NCAA compensation rules not at issue in the case, writing that sports traditions “cannot justify the NCAA’s decision to build a massive money-raising enterprise on the backs of student athletes who are not fairly compensated.” The tide was finally turning.

Nine days later, the NCAA’s board of directors voted in favor of allowing student athletes to profit from their name, image, and likeness. The body’s interim policy put down few firm rules governing how this would work, however, unleashing a chaotic free market in which donor collectives competed aggressively for top talent. The first endorsement deals were signed at 12:01 a.m. on July 1. Student athletes started hawking chicken wings, tea, razors, pet toys, fireworks, dental services, moving companies—you name it. Olivia posted a TikTok of herself dancing in front of a headline about the new policy to Destiny’s Child’s “Bills, Bills, Bills.”

Less than two months later, she was the first college athlete to sign with WME Sports, the athlete-focused division of the behemoth talent and media agency. In September, she announced her first deal, reportedly worth six figures, with Vuori, an activewear brand. Olivia has since added deals with L’Oréal, Spotify, Forever 21, Motorola, American Eagle, Grubhub, ESPN College GameDay, and YouTube. (Earlier this year, Olivia received backlash after endorsing Caktus artificial intelligence, but she defends the ongoing deal: “I felt it was a good partnership because AI is the future.”) On3 now projects she makes an estimated $3.4 million per year. “To be able to be in college and make seven figures is awesome,” Olivia says in LSU’s palatial practice gymnasium. “And the fact that people before me couldn’t do it…that sucks.”

Olivia takes classes and trains during the day, and creates content for social media at night. She has the help of her older sister, Julz, who started at LSU one year ahead of her and is, Olivia says, “sometimes the brains behind the operation.” They come up with ideas for videos together and film them, and then Julz often edits them while Olivia is at practice. Julz graduated from LSU this spring, but she isn’t currently looking for a job in her major, kinesiology; instead, she’s working in Livvy Land as a paid employee while building her own social media business to help other student athletes to maximize their NIL.

The sisters lived in apartments down the hall from each other until recently, and they hang out all the time. Olivia says the apartment she shares with three roommates is “disgusting,” which strikes me as one of the most normal college-kid things about her. She’s majoring in interdisciplinary studies, a combination of three minors: communications, sociology, and leadership. She’s on the academic honor roll. To her friends and family, she’s Liv or Olivia, rarely Livvy. She doesn’t currently have a boyfriend, but says that if and when she does, she’ll keep that part of her life private. Olivia says she’s careful when she walks around campus, conscious that she has eyes on her. Sometimes other students approach her for photos, but mostly they’ve gotten used to her around here. Still, she doesn’t attend classes in person “for safety reasons,” she says. “There were some scares in the past, and I just want to be as careful as possible. I don’t want people to know my daily schedule and where I am.”

She has cause for concern. At LSU’s opening meet of the 2023 season, an away meet at the University of Utah, a mob of unruly young male Livvy fans chanted wildly during the competition, disrupting the performance of other gymnasts. There were also reports of gymnasts being harassed as the estimated 100 to 200 men demanded to see Livvy; one was told she wasn’t Olivia but “she will do.”

Olivia didn’t even compete at the meet—she was injured and just there to cheer on her teammates—nor did she see the chaos outside. “It was our first meet of the season. I knew that my success had grown from the years prior, but I did not expect there to be that many people out there to see me and my team,” Olivia says. “I didn’t really realize until after the meet when I saw the videos of it. I was like, ‘Holy moly.’” On Twitter, she asked her fans to be “respectful,” reminding them that she and the other gymnasts are “just doing our job.”

In the aftermath online, some commenters levied the same tired, sexist line at Olivia that we’ve all heard before: She was asking for it, they said, pointing to what she wears and posts and ignoring that she dresses and behaves like her peers, a leotard is her required uniform, and she is in no way responsible for the unhinged behavior of her fans. “It’s not a girl’s responsibility how a man looks at her or how he acts, especially when you’re doing your sport and that’s your uniform. I can’t help the way I look, and I’m going to post what I feel comfortable with,” Olivia says. “It’s hard to handle at times, definitely, because I am just a 20-year-old student. I think people do forget that.”

The university’s athletic department hired private security to accompany the team to meets for the rest of the season, and there were no further incidents. LSU Gymnastics head coach Jay Clark, who is “not a fan of social media” and yet finds himself coaching the NCAA’s biggest social media star, says what happened in Utah is something he’s feared. “I’ve always been afraid of the idea that social media takes what otherwise would be a fairly localized fan base, and now it’s everywhere. As awareness of our sport got greater, as awareness of Olivia got greater, as NIL deals got bigger, it seemed kind of like the perfect storm was brewing,” he says. “I just want to coach. I don’t want to have my head on a swivel worried about if somebody is coming out of the stands.”

Still, he doesn’t yearn for the pre–social media days, because he knows how much better things are for his team now overall. “I’m excited about the exposure they’re getting, that they’re getting their just due for the work, athleticism, and things they accomplish—that part is tremendous,” Clark says. “I don’t look back and long for the good old days, so to speak, because the good old days weren’t so good. No one was in the stands, no one cared what we did, and nobody was making any money.”

Earning money in college is especially important for women athletes who don’t stand to make anywhere close to what men make after college. Last year, some had speculated that UConn basketball star Paige Bueckers would enter the WNBA draft, forgoing her senior year. But staying in college will likely be more lucrative: Bueckers stands to gain about $1 million from her NIL this coming year, four times as much as what she might make in the WNBA if she were offered 2023’s highest salary: approximately $235,000. For gymnasts, who have no pro prospects and typically age out of the punishing sport by their early twenties, college could very well be their prime earning years.

Of course, not everyone is earning like Olivia. Of the approximately 520,000 current student athletes, the New York Times estimates 519,000 are “making nothing at all.” Male basketball and football stars comprise most of the top NIL moneymakers, and it’s not always the best athletes who get the most attention. Olivia has been plagued by injuries to her shoulder and shin. This season, she often cheered her team on from the sidelines with the aid of a knee scooter. As such, she readily admits there are women on her team who “are better than me,” and yet because of her following, she’s by far the top earner.

She isn’t to blame for the inequity, but she wants to be part of the solution. To that end, she recently launched the Livvy Fund to create opportunities for other women student athletes at LSU to connect with brands and secure endorsement deals. “It’s really important to raise as much money and awareness for these incredible women athletes who won’t have the same opportunities after college,” she explains.

The idea is that brands would put a portion of the money they give Olivia in an endorsement deal toward the fund, and then Olivia and her team would use that money to give financial opportunities and business guidance to women athletes, which would, in turn, hopefully lead to future contracts and deals for the Livvy Fund-ed athletes. “There are collectives in NIL, which mostly go to the men’s sports, and I think that’s extremely unfair,” says Olivia, who had just signed her first contract that designated money to her fund when we met. “So I wanted to let other women student athletes know that anyone can do this—you can do this. This is just the beginning, truly.”

Her mom says the inspiration for the fund came, perhaps surprisingly, from Olivia being treated cruelly online. “It made her start to think about what her bigger message was,” Kat says. “It was like, ‘All right, you’re in the spotlight, good or bad, you get all of this attention, what is something that you want to do with it?’ And that started the conversation of how she wanted to give back to other women in sports.”

As Olivia thinks ahead to her senior year, she looks past next year’s national championships (hopefully a win) to whatever comes after she leaves gymnastics behind for good. “I know it’s coming to an end, so I’m trying to take in every single last memory I can, but I’m also excited to see what the future holds,” she says.

There could be a product line; an acting role; a book—the options are limitless when you have a following like hers. She is considering moving to Malibu, New York City, or Florida after graduation. “Probably I’ll end up near a beach, I’m guessing,” Olivia says. “Then I can just honestly go back to what I started doing. I could flip around on the beach. I could. That’s how it all happened. All of this…” trailing off with a touch of wonder as she reflects, “All these followers and this life.…”

Hair by Ben Skervin for Colorwow; makeup by Jessi Butterfield for Chanel Beauty.

This article appears in the August 2023 issue of ELLE.

Deputy Editor

Kayla Webley Adler is the Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. She writes and edits cover stories, profiles, and narrative features on politics, culture, crime, and social trends. Previously, she worked as the Features Director at Marie Claire magazine and as a Staff Writer at TIME magazine.