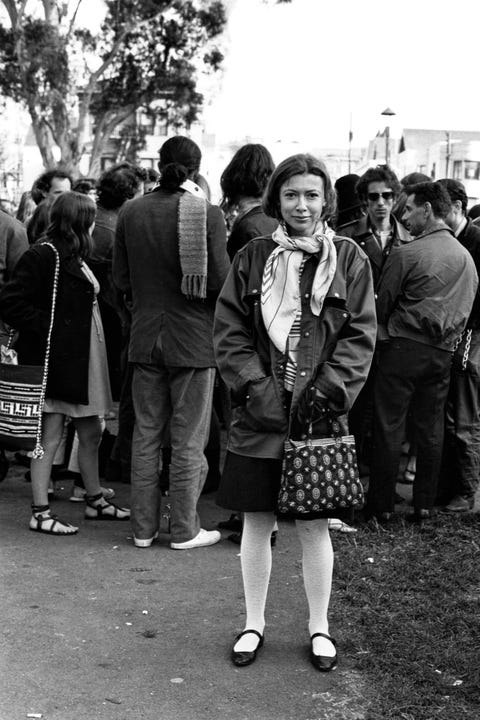

Fundamentally, Joan Didion believed in the plain act of writing—even above great writing, though hers was exquisite. The foundation was simply to do it, to use your abilities and vision, to continually sharpen them, to keep going. To be, as she so aptly put it, “a person whose most absorbed and passionate hours are spent arranging words on pieces of paper.” She wasn’t ceremonious about it, despite the fact that she was able to funnel intense, hard-to-articulate things into admirably accessible and compelling prose. She was measured but maintained a sly sense of humor, even when chronicling the most grim or worrisome realities. Having authored novels (five), books of nonfiction (10), and a play, she made complex matters sharply intelligible without being reductive. She tackled the utter devastation of personal loss, as a subject, in a way few have. She exuded calm poise—epitomized in her black-and-white portrait by Julian Wasser, in which she leans against her Corvette Stingray, shoulders convexly folded in, brow slightly furrowed, cigarette lit—that belied the turmoil she worked out on the page. Her porous influence has been felt throughout her lifetime, and all over again in the outpouring of grief over her death.

Nothing was beyond the scope for Didion—her writing was founded upon her trust in her powers of observation and immersion. She was cool in the sense of temperate—she knew what she was shaped by and explicitly detailed things without being dispassionate or bleeding heart, accomplishing shrewd reporting without compromising humanistic vulnerability. She was confident in her gaze because every writer ultimately must be: even when you’re a discerning professional, you are only ever really yourself. She is described as “legendary” and “towering” and “radical”—but what makes her so is that she clearly never thought of herself in lofty terms, but practiced the brass tacks of the métier.

“Her commitment was not greater than her fear and dread,” noted Hilton Als in an introduction to her essay collection Let Me Tell You What I Mean, “it was equal to both.” Didion wasn’t shy about expressing this fear and dread, the searching energy that can swiftly dead-end at a feeling of imposter syndrome. But she didn’t use writing to express a point of view, rather inversely to draw herself out, to serve as her own crystal ball. In The Center Will Not Hold—the 2017 Netflix documentary about her life orchestrated by her nephew, actor Griffin Dunne—she stated: “The reason I had to write it down is that no one had ever told me what it was like. It was a coping mechanism.”

Her magazine experience fashioned and strengthened her as a craftswoman, and made her nimble. It was “not unlike training with the Rockettes,” she mused in the essay “Telling Stories” (initially published in 1978 in the now-defunct magazine New West). It was where she came to think of “words not as mirrors of my own inadequacy but as tools, toys, weapons,” she wrote. “We were connoisseurs of synonyms. We were collectors of verbs.”

She didn’t gloss over moments of creative alarm: sometimes, “I believed that I would be forever dry. I believed that I would ‘forget how,’” she confessed. She experienced brush-offs—Redbook once sent her a rejection letter that deemed her work ‘just too brittle.’ “There is always a point in the writing of a piece when I sit in the room literally papered with false starts and cannot put one word after another,” she stated in the preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem. In her 1989 piece “Some Women” (which served as a prelude to Robert Mapplethorpe photographs), she wrote about that “fear that the fragile unfinished something will shatter, vanish, revert to the nothing from which it was made.”

The way to overcome this was giving herself “room in which to play with everything I remembered and did not understand.” That room was never comfortable, as the punishing margin of error was relentless. But to attempt to heal from the ache of being a rudderless human, there was no alternative (aside from alcohol, that is): “Working did to the trouble what gin did to the pain,” she wrote. Her process was always: go forth.

In an era where mentors are impossible to come by, she stands in as the perfect writing teacher—perhaps this is why she is so beloved. Her sagacious advice is minimal, and close to the bones: the prose version of Nike’s “Just Do It.” Didion was no-nonsense: not in a hall monitor way, but the person who would tell you a brash thing in a flat tone, like that friend who will let you know if something just doesn’t flatter you. She embraced what she felt, based on who she was at the time and what the present moment appeared to convey.

She was a kind of antithesis to the extravagance and glamor of another Los Angeles writer figurehead, Eve Babitz, whose death is also being mourned (although, as her obituary stated when she died a few days ago, her writing reached a slightly different crowd: “Babitz often found magic where Didion saw ruin”). In a depressing death triptych, bell hooks, who also passed recently, expressed takes that had some overlap with Didion’s—like the need to write by virtue of sheer absence. In Feminism is for Everybody (2000), hooks stated: “I had to write it because I kept waiting for it to appear, and it did not.” Her approach to language too is of a piece with Didion’s: “I want to be holding in my hand a concise, fairly easy to read and understand book; not a long book, not a book thick with hard to understand jargon and academic language, but a straightforward clear book—easy to read without being simplistic.” Didion positioned herself similarly: “I am not in the least an intellectual, which is not to say that when I hear the word ‘intellectual’ I reach for my gun, but only to say that I do not think in abstracts.”

Didion’s essay “Why I Write” (which first appeared in The New York Times Magazine in 1976, and was reprinted in the collection Let Me Tell You What I Mean) doubles as a writer manifesto, a rousing encapsulation of her approach: “In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want…but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully.” But her bullying wasn’t cruel—it was a wise reckoning, and we are lucky its reach will knock us sideways with every fresh read and re-read.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io