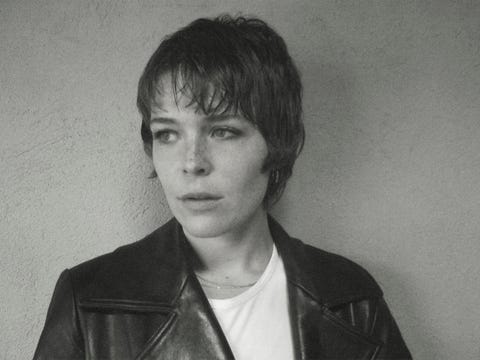

On her sophomore album Hold the Girl, Rina Sawayama, the breakout British artist known for the mashup style of her 2020 debut—Y2K pop meets nu-metal meets ‘90s R&B—doubles down on her sonic signature. This time, she hones in on the sounds of early 2000s adult contemporary radio, updating them with stadium-sized drum fills and stomping club beats to tell the story of reparenting herself.

From the acrobatic “ay-ee-ay-ee-ay” choruses of “Catch Me in the Air” and “Forgiveness” to the acoustic country-pop sweetness of “Send My Love to John” and high-gloss sheen on piano power ballad closer “To Be Alive,” Hold the Girl creates a world of vintage pop songs for the emotionally literate millennial seeking to recapture the joy of music from a 2000s-era childhood with an adult perspective on the decade’s ills.

If 2021 saw the mainstream revival of pop-punk with albums from artists like Olivia Rodrigo and Willow, then 2022 marked the glossy, glorious return of adult contemporary. That’s exactly the music I remember from my own childhood, sitting driver’s side in the very back bench seat of my mom’s ‘96 Town and Country, the voices of Sheryl Crow, Faith Hill, and Shania Twain belting the chorus again and again, building on it, vocal flourishes swooping out of the overdubs. This was deceptive music, its acoustic guitar and piano-driven pop the basis for strong voices to drive that feeling of venturing into new beginnings (“I’m going to tell everyone to lighten up”), second-guessing your good luck in love (“Baby, isn’t that the way that love’s supposed to be?”), or giving yourself over to it completely (“And for your love, I’d give my last breath”) to the fully saturated brink.

Like the decade of romantic comedies that preceded it, the adult contemporary genre was home to music that excavated the feelings of women in all their seriousness, leaving melodrama to the straightforward feel-good-chasing Hot 100 pop hits, an ephemeral taste of emotion that lasts as long as a song, but doesn’t linger. Songs spun on adult contemporary radio were all about that leftover residue of feeling: women torn apart and incapable of letting it go—long past the point of anyone else caring—falling in love again with the shadow of the past creeping over their shoulders, or exploring the clarity of feeling that comes after personal disaster. Ultimately, it asks the question: Who am I now that I know I can survive this?

This year’s albums from a new vanguard of pop musicians—Sawayama, Maggie Rogers, and L.A. three-piece MUNA among them—offered similar answers about reclaiming their agency and freedom, using adult contemporary as the base of their sound and building on it with their own array of influences. Sawayama added the arena rock of the ’80s and the neo-futurist visions of early Max Martin; Rogers took the new wave lifeblood of New York and pushed herself into distorted territory ruled by men when she was growing up; MUNA kept the dark pulse of the nightclub from their earlier albums for an electronic and heartfelt effect.

All three acts are on the trajectory from arena-opener to big ticket billing, not merely supporting the likes of Taylor Swift, Lorde, and Kacey Musgraves, but filling those seats themselves in the next few years to come. Their albums are all the product of universe-mandated self-reflection stemming from the beginning of the pandemic, and in reaction to the whims of fame and success.

For Sawayama, that manifested as going back to her childhood and using the popular music of that time (and the country-pop of Shania Twain in particular) to relieve herself of old traumas, creating something she didn’t have growing up as a queer, Asian girl living under Section 28 in the U.K. The best example of that is the rollicking “This Hell,” but the whole resulting album—its power ballad beginning swept into a rave and industrial rock middle act, barreling straight back to stretched out, heartfelt pop—leaves you winded, like leaving a therapy appointment all cried out. “If I can heal someone around me or someone that I don’t know with the songs I write, and I’ve been given an opportunity to do so,” she told ELLE in June, “why wouldn’t I take it?”

For Rogers, weighed down under the intense pressure to deliver her debut and the non-stop years of touring that followed, holing up in Maine at the beginning of the pandemic was a chance to return to the root of her creative process, making music as a mode of being rather than in service to an industry that expected something from her.

“I think that I came back to songwriting in a way that feels as vulnerable and intimate as it did in high school or college, when I was making songs just for myself,” she told ELLE.com earlier this year.

Surrender, her sophomore album released in July, is a full-throttle offering, pushing everything to the brink of feeling: her voice, untamable on the single-take recording of “Horses”; the production, its stretched contrasts between the slowed down, Vanessa Carleton-esque opener “Overdrive” and new wave frenzy of “Shatter”; and its sentiments, self-possessed on “That’s Where I Am” and unselfconsciously optimistic on the acoustic slow burn “Begging for Rain” and closer “Different Kind of World.”

Rogers made the sort of album she wanted to hear live in a period without shows, but also maybe one that creates a vision of her future as a more centered person, confident in her place in the music industry. “I think that’s so much of what creativity is, right?” she told ELLE.com in July. “You create the world you want to see, and these acts of imagination inevitably become super hopeful.”

For MUNA, their third, self-titled album was the result of a professional shake-up, an unexpected exit from major label RCA at the beginning of 2020 that sent Katie Gavin, Josette Maskin, and Naomi McPherson back to the drawing board and wondering what it would sound like to make music as if they were “a huge dyke boy band.”

“I really love the idea of reimagining our childhoods, but casting ourselves as the cultural icons that we wish we could have had,” Gavin, the group’s lead singer, says over Zoom in December.

“It would truly have meant the world to me as a 12-year-old, 13-year-old to see a band like us,” McPherson told ELLE.com back in June.

It led to a certain amount of joyful irony when MUNA dressed up as Lindsay Lohan’s band Pink Slip from the movie Freaky Friday for their tour-ending hometown shows at the end of October. For a person like me who started forming memories and seeking out my own musical interests at the turn of the century, it seemed like the only bands without any cis men in them (and where the members played instruments, unlike pop girl groups like Spice Girls and Destiny’s Child) were fictional, like Pink Slip or Josie and the Pussycats. Doubtlessly, that era was more defeating for McPherson, who is nonbinary. But even Maskin, who recalls going to see the band Heart perform while growing up, says there was something reductive and tokenizing about the way the rock band was talked about at the time. She notices the oversimplifications about MUNA are akin to that too.

“It couldn’t be just like a woman who’s performing rock music, it’s like ‘Heart was like the girl band,’ of that time,” she says. “I feel like there’s always some sort of token girl band … and Heart was so sexualized.”

Gavin expresses similar unease about what she internalized about the music industry and her chances of succeeding in it when growing up.

“I was so sure that the keys to the kingdom were held by powerful men, and they were only given to the women that they wanted to fuck,” she says.

Let’s be clear: MUNA are fuckable. But the kinds of people losing their minds over the band’s chemistry on stage are probably not the same kind of people who could make or break artists’ careers in the 2000s based on their desirability to cis male record execs. These days MUNA are under the wing of fellow queer musician Phoebe Bridgers and her label, Saddest Factory, and they’ve made a record of gleaming pop music without forsaking emotional intimacy, the lyrical lived experience of queer existence, or shedding their more adventurous electronic impulses. On their self-titled album released this summer, the wind-in-your-hair rush of “Silk Chiffon,” an ode to letting yourself fall in love with a girl that sounds destined for a 2000s teen rom-com (and ended up in one this year), can sit right alongside the full-throated “What I Want” and the downtempo, country-pop ballad “Kind of Girl.”

“There’s something kind of beautiful about revisiting the sounds of our elders and trying to honor that legacy by struggling to be as full of the versions of ourselves [as possible],” Gavin says. “The record that we made sounds like an early 2000s record, but it’s a lot more explicitly queer than an early 2000s record would be able to be.”

Rina Sawayama, Maggie Rogers, MUNA, and so many other artists who might have felt excluded by the 2000s’ essentialism in gender and sexuality have grown up to make great music this year—music that builds on the adult contemporary tradition of acoustic guitar and piano music that was popular at a time when attitudes were quite different. iLe examined the sociopolitical landscape of the world and her place in it as a Puerto Rican woman on the Cubist self-portrait Nacarile; the U.K.’s Connie Constance dissected the power dynamics of interpersonal relationships as a Black woman on Miss Power; SZA took an acoustic turn on SOS. to get realer than ever about insecurities and unflattering romantic impulses.

Outside of the music world, early aughts nostalgia began to filter into the mainstream this year, with young audiences on TikTok excited about the aesthetics of mini-skirts and low-rise jeans while glossing over how those styles were born in an era that emphasized impossible beauty standards around thinness and whiteness and femininity. Growing up in the 2000s? That decade was pure brain poison. But if we can resist an oversimplification of the past, if we can deconstruct it and build it anew in ways that better serve our adult selves as Rina Sawayama, Maggie Rogers, and MUNA did in 2022, then vintage sound can be fertile soil to plant a garden in.

Cyrena Touros is a critic and reporter who writes about music, culture, and digital society.