To be Black often means to be seen as “the other.” This is especially true when it comes to our hair care regimens. So when a brand comes along that not only caters to our unique textures, but also adds a sense of ease to our routine, we start to feel like we’ve found a place where we belong. We begin to feel like the sometimes lengthy process of caring for our hair can be enjoyable.

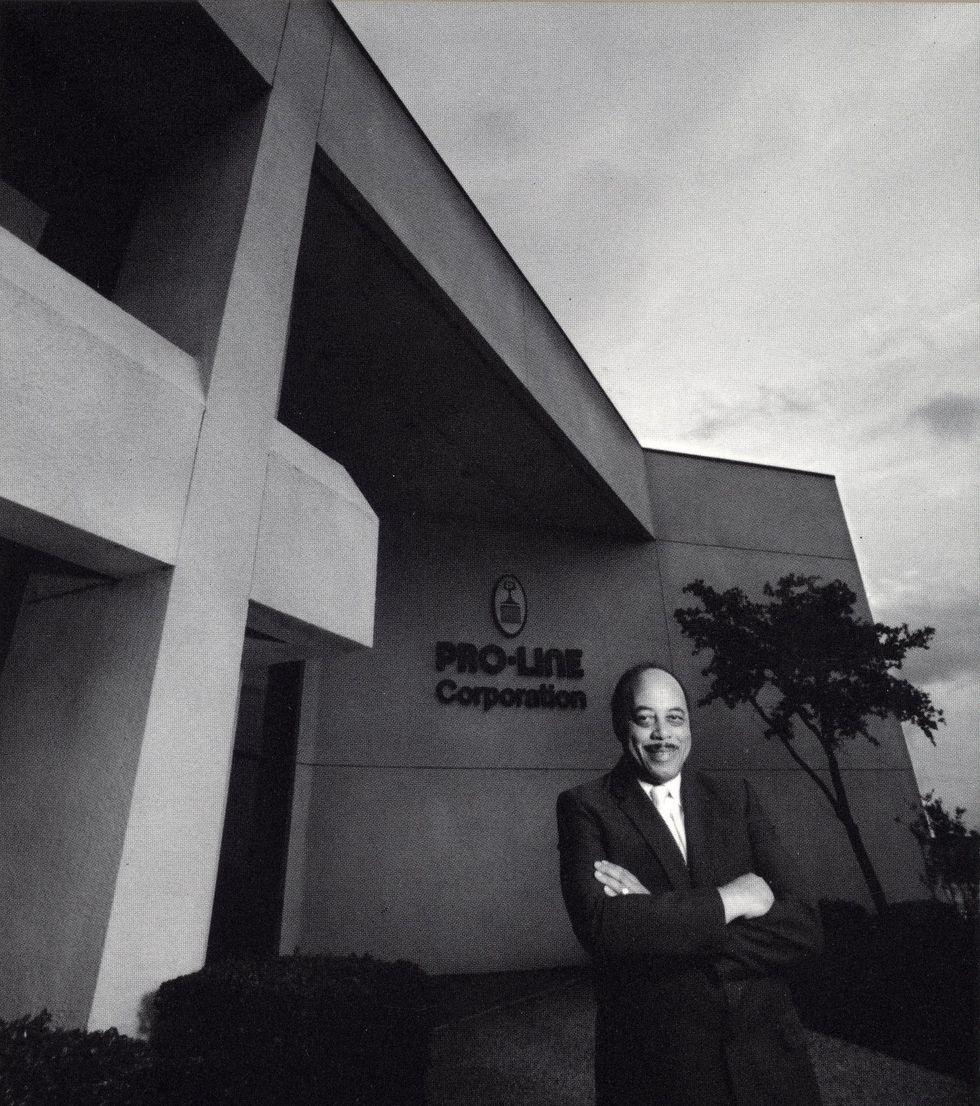

That’s the idea Comer Joseph Cottrel Jr., creator of Pro-Line hair care products, had in mind when he created the company in the early 1970s—the decade we saw the first wave of the natural hair movement blossom. While he wasn’t the first entrepreneur to create a hair care line catering to the Black demographic, he was among the few at the time who formulated products specifically made for afros. “It was a special time for Black people taking pride in their natural hair,” says his daughter, Renee Cottrell Brown. “Right away, he came out with an [oil sheen] product that did really well.”

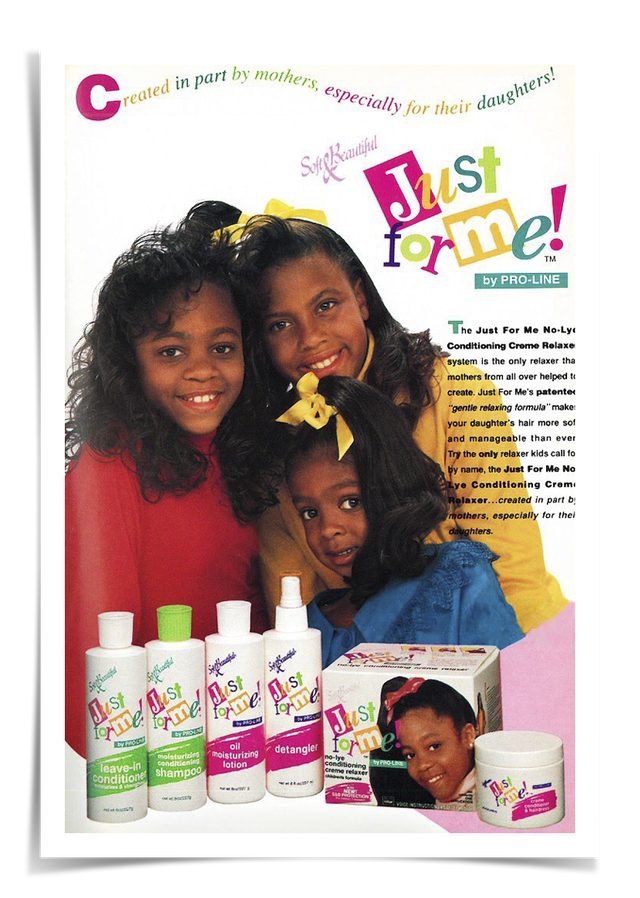

The success of her father’s line led Cottrell Brown to get into the hair care biz as well, helping to develop and launch Just for Me relaxers in the early 1990s—a time when straight and sleek hair was in. What made it appealing to customers was that the line was both affordable and accessible. Being sold at mass retailers like Walmart made it easy for many Black consumers, specifically Black mothers, to pick up a box whenever it was convenient for them. Plus, the easy-to-follow audio and written instructions made at-home chemical styling something anyone could do without breaking the bank—or a cosmetology license.

But the true secret sauce, Cottrell Brown shares, was once again creating an intimate relationship with their target audience. “We spoke to the consumers—teen girls—and the consumers’ mothers,” she shares. “We knew mothers would be the ones to purchase the products, but that they were also influenced by their daughters. We researched what music [the daughters] liked, their interests, etcetera.” The result? Mass success and long-term customer loyalty.

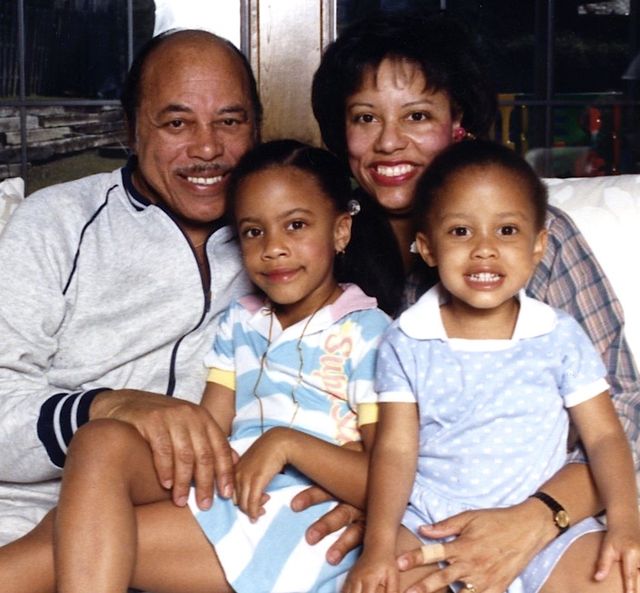

However, with the second wave natural hair movement taking over in the 2010s, relaxer sales began to dwindle. But by 2020, Autumn Yarbrough, daughter of Cottrell Brown, kept the family’s legacy going by launching Nu Standard, a professional line of both at-home and in-salon hair care treatments that addressed common issues for the modern consumer, like dryness and breakage.

Within the span of three generations, this family has not only created a legacy in the Black hair care space, but also proven that understanding the intimate, and ever-evolving needs of the consumer is the key to longevity.

ELLE.com sat down with Cottrell Brown and Yarbrough to discuss the evolution of the family business, why their collections have always resonated with the Black consumer, how new founders can find their place in a rapidly-growing industry, and more

Why has hair care been such an important part of your family’s lineage?

Renee Cottrell Brown: It’s a family business, and I grew up in the business. My father initially started the Pro-Line business with partners and started selling door-to-door as well as in the salons. In fact, when I was in high school, I started helping sell Pro-Line door-to-door. My father eventually bought-out his business partners and turned it into a true family business, which also included my father’s younger brother, James Cottrell—a true salesman at heart.

What sparked interest in this particular industry?

RCB: It boils down to a simple observation during his time in the Air Force. While running a PX [post exchange], he noticed there were no hair care products for African American servicemen and women. Seeing this gap, he saw an opportunity to serve the African American community by providing products that were otherwise missing. This realization while in the military sparked his venture into the hair care industry.

Before he formally started the business, however, he had other small businesses, like painting houses. He was always successful with every career he took on, but was searching for a more entrepreneurial career route. He had been into male barber shops, and they talked about the needs of the male consumer at the time. He also had business partners that had formulas for the products, so he knew he could help sell and elevate what they had already started, and that’s essentially how it all began.

Autumn Yarbrough: The most important part during my grandfather’s time was providing access to products that weren’t typically accessible to the African American community. It provided belonging. It provided access for women to have products at an affordable cost. It gave them a sense of belonging in beauty. That’s my family’s legacy. We want to provide a sense of belonging in beauty, especially for women.

Renee, your father became successful in a time when Black people did not have access to accelerator programs, the internet, or capital. How did he reach customers?

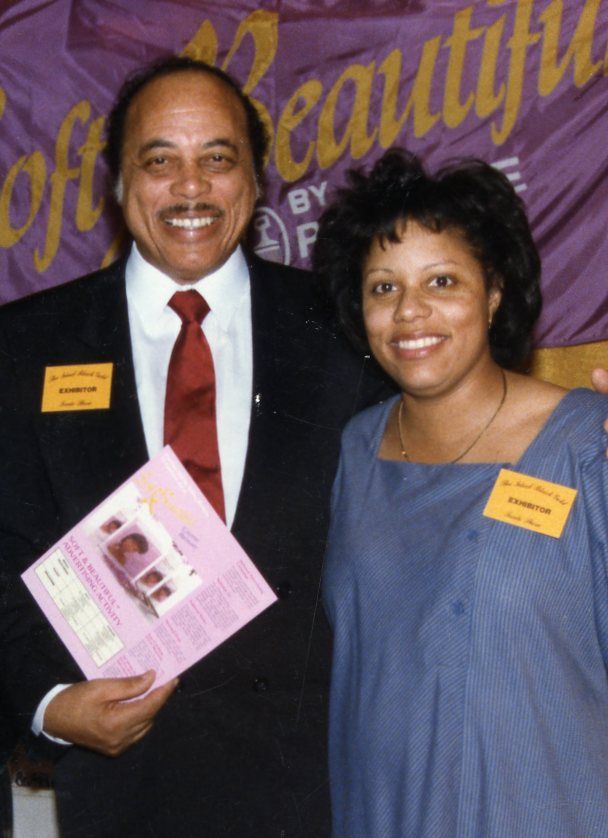

RCB: In 1971, a big year for celebrating natural Black hair and afros, my dad started his hair care company. It was a special time for Black people taking pride in their natural hair. My father was absolutely ahead of his time and had a knack for understanding consumers —what they needed, wanted, and how to reach them. In fact, he was the third company that came to market with oil sheen, but was more successful than others, because he out-packaged everyone.

The Soft and Beautiful product line featured a foil gold pick on the product, which made it stand apart on store shelves and made it look very expensive, although it was affordable. There was also a strawberry fragrance in the product, which at the time was a hot scent. These seemingly small details paid off in a very big way, because everyone wanted his product because of the attention to detail; and so, he quickly sold out of the product and became the number-one seller.

Your father and grandfather Comer Cottrell has also been credited not only with bringing the Jheri curl to the masses, but also making it achievable at home. What did this teach each of you about the importance of adding ease to the customer experience?

RCB: With Just for Me, I was highly involved in this development, and we wanted to go beyond simply providing consumers with an instruction sheet. So, we created a cassette tape for customers to play the instructions and have step-by-step guidance without a salon professional to ensure they achieved the correct results with the relaxer. We also provided them with a regimen for maintenance, which is something else no one was really doing at the time. It was a game-changer and unlike anything that had been done in the industry at that point and was a helpful guide for more than three years. After three years, we removed the cassette from the packaging, because professional and home stylists were acclimated and knowledgeable about the product.

AY: I’ve always looked up to my mom. She’s a great businesswoman and a leader in our community. Watching her build a sense of togetherness for our family and giving us a strong feeling of belonging, especially when I was young, really meant a lot to me. She really cared about making sure women had what they needed in beauty products—things that were safe, didn’t cost too much, and were easy for people to get. Seeing her think about what teenage girls like me needed was pretty amazing. My mom always looked ahead, making sure we used the best stuff in our products and figuring out what was missing in the beauty market. She worked hard to make sure all women felt like they had a place in the beauty world. Growing up around such strong and inspiring women was really exciting. Now, my goal is to run a business that supports women, makes products for everyone, and solves real problems.

Just for Me relaxers dominated the ‘90s. Tell me more about the development process and why you think this particular brand was able to resonate so deeply with Black women and girls?

RCB: Simply put, market research. We are believers in research and consumer research. We spoke to the consumers—teen girls—and the consumers’ mothers. We approached research this way, as we knew mothers would be the ones to purchase the products, but that they were also influenced by their daughters. The end consumer was always going to be the child; because if the child did not like the product, the mother wasn’t going to buy it again.

We also wanted to stay on top of young girls’ minds. So, one of the first things we did was develop the Just for Me Club, similar to a Girl Scouts concept. Not everyone could be a Girl Scout, but anyone could be in the Just for Me Club. We researched what music they liked, their interests, etc. And we found they loved the group, The Boys. With this mindset and knowledge in-hand, we set out to reach as many young girls as possible and did a tour with our retailers in top African American markets, and if you went in and purchased a Just for Me product, you’d receive a ticket to The Boys concert ticket. It was wildly successful.

Times have definitely changed, however. As more Black women have gone natural over the past two decades, we’ve seen a decline in the popularity of relaxers and have been made aware of some of the health concerns. How do you feel about this shift?

AY: The problem with hair relaxers and the lack of long-term research and development isn’t just a concern for the brands and the U.S. Health Department. It’s also something that ingredient suppliers, contract manufacturers, and clinical research labs need to take seriously. Everyone involved in the industry should care about this. It’s important for all of us to work together to make sure we’re constantly testing and improving our products to ensure they’re safe and effective for the African American community. This means making sure the products meet modern health and environmental standards. Everyone in the process should be just as committed to making sure the African American community isn’t overlooked when it comes to product quality.

RCB: To compliment what Autumn said, before we even developed innovative ways to communicate our hair care instructions, we were providing our customers with “do’s and don’ts,” and were firm in our communication about the correct methods of using our hair care products. We were clear in communicating that not following our care instructions could sometimes result in a negative outcome. Safety in the products and safety for the consumer is always top of mind for us.

Autumn, in 2020, you launched NU Standard. Tell me about the line and how your family’s legacy influenced the creation of this brand.

AY: At NU Standard, our mission is deeply rooted in my family’s legacy of fostering a sense of belonging and inclusivity, especially for the Black community, while ensuring our products cater to everyone. This mission represents the unfinished business I am determined to carry forward: to redefine inclusivity in the industry starting at the research and development stage. I want to ensure that the Black and textured hair community is never left out or last in line.

Taking inspiration from my grandfather, who also valued the importance of working with professionals, I’ve redefined NU Standard as a “restart legacy business.” My husband and I have taken it upon ourselves to fully fund and revitalize the business, placing a significant emphasis on forging and nurturing relationships with haircare professionals. We firmly believe that the support of professionals is crucial in overcoming the unique hair challenges. It’s hard to find anyone who has navigated the complexities of hair care alone. Whether it’s the latest product or technique, the expertise of a cosmetologist is invaluable—they not only understand the science behind hair but also provide personalized guidance on the journey to healthy hair.

Some say the Black hair care market is oversaturated. Do you still think this is a good avenue for Black women entrepreneurs looking to build both wealth and legacy?

AY: Yes and no. It’s definitely a positive that people of color and those with textured hair see a path to success in the hair care industry. Icons like Madam CJ Walker, Annie Turnbo Malone, George Johnson, Ed Gardner, and my grandfather paved the way. However, the challenge in a saturated market is to remain innovative and responsive to the specific needs of Black women. These needs, or pain points, are always evolving. The real issue with oversaturation is the plethora of similar products that fail to innovate. Let me emphasize that innovation isn’t just about the science and R&D; it’s also about how you position your product. With Hydrasilk, we’ve focused on hydration because it’s a widespread issue that’s not getting enough attention across the board.

When Pro-Line was first developed, there was a distinct need, as mass brands only catered to straight textures. Now, mainstream lines cater to everyone. Should contemporary Black-owned companies be expanding their product lines to meet the needs of all consumers?

AY: As a Black-owned brand, it’s vital to advocate for and achieve cross-over appeal. This means actively seeking opportunities for broader visibility and recognition from retailers and media. It’s important to challenge and overcome any attempts to pigeonhole our brands, especially when our products are designed to cater to a diverse audience. Highlighting the versatility and inclusivity of our offerings not only broadens our market but also reinforces the importance of diversity and representation in the industry.

As Black women like Monique Rodriguez of Mielle, Beatrice Dixon of Honey Pot, and Pinky Cole of Slutty Vegan continue to shatter glass ceilings, it underscores the importance for brands to be evaluated based on the quality of their products rather than the appearance of their creators. This journey requires us to persistently challenge stereotypes and advocate for inclusivity. Our efforts must focus on ensuring that [Black-owned] brands are recognized for their innovation, effectiveness, and contribution to the market, not just the racial or ethnic background of their founders. By doing so, we honor the legacy of pioneering Black women entrepreneurs and pave the way for future generations to thrive in a more inclusive and equitable market.