During a recent meditation session, my deep lower-belly breaths and silent prayers into the dark abyss behind my eyelids were suddenly interrupted by “Eye of the Tiger” lyrics blasting loudly in the back of my mind: “Rising up, back on the streets. Did my time, took my chances…” I welcomed this sonic intrusion on my yoga mat only because the iconic Rocky franchise (RIP Creed) is of supreme importance to my family history. My dad introduced my sisters and me to the 1970s blockbuster series when we were just little girls. Our fandom runs so deep that we have memorized all the lyrics to the Rocky IV soundtrack and are known for impromptu performances of “No Easy Way Out.” Fast forward a few decades later, as I’ve started to investigate the aches and pains of my mid-30s, one of my most nagging ailments has been, ironically, a muscle spasm lodged in my left serratus anterior, known as the “boxer’s muscle.” It’s the muscle group employed by the body when throwing a punch. My deep dive into my own chronic pain led me down a fighter’s tale I didn’t expect, starting with my own veteran grandfather.

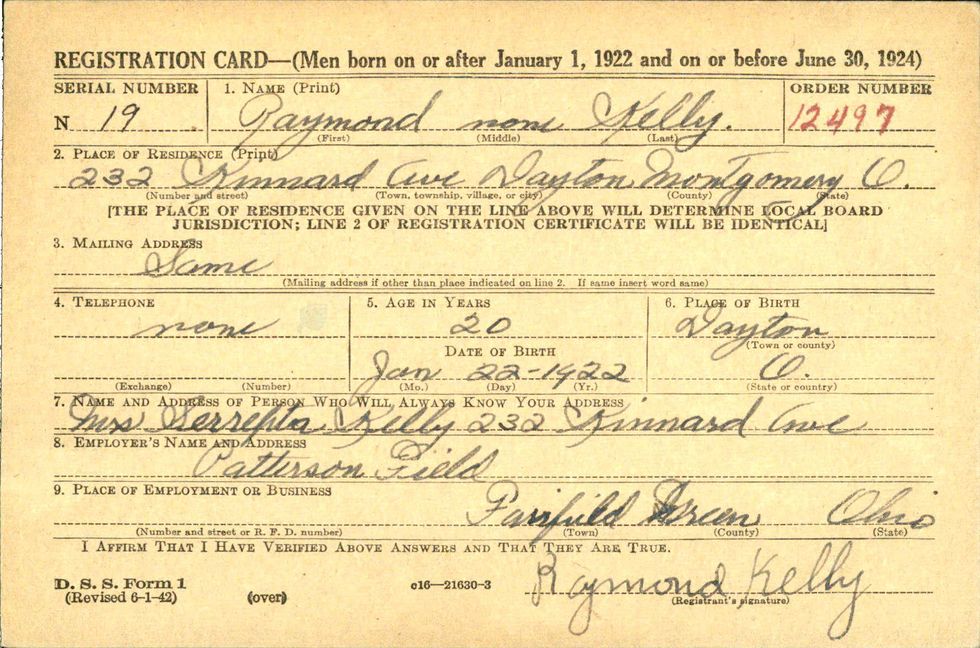

Raymond Kelly Sr. was drafted into World War II as an army truck driver when he was 20 years old and living in Dayton, Ohio, according to documents I obtained through Ancestry.com. I didn’t expect to burst into tears seeing my grandpa’s handwriting, for the first time, on a tan-colored 1940s draft card as genealogist Nicka Sewell-Smith walked me through his buried life history. To my surprise, a well of untapped grief around never knowing my paternal elder had been living inside of me all along. Before I was born, my grandpa died at the age of 54, after suffering a stroke at 43—a little over 20 years after he was drafted into war. But, as the circle of life goes, my tears of grief turned to tears of joy when Sewell-Smith shared with me that she found a newspaper clip from the 1930s that listed a little-known fact about my grandfather: He was a lightweight entree into a Golden Gloves boxing competition in Dayton, Ohio. My dad cracked up when I shared the discovery with him, because, unbeknownst to my bloodline, Raymond Kelly Sr. was a young boxer before he was drafted. Two generations later, I can’t help but wonder what unresolved ghosts from fighting and war are still lingering in my own chronic aches and pains.

Research suggests that trauma, caused by disaster, adverse childhood experiences, chronic stress, and physical and emotional abuse, can alter the way genes are expressed in a parent’s DNA so significantly that it can affect the gene expression of future generations. One of the most significant studies exploring intergenerational trauma transmission to-date was based on a cohort of Holocaust survivors and their families. In a 2020 study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry, researcher Rachel Yehuda, director of the Center for Psychedelic Psychotherapy and Trauma Research at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and team examined blood samples of Holocaust survivors’ offspring and compared it to blood samples from Jews whose parents weren’t in the Holocaust. Researchers found, by comparing the two samples, that the blood of Holocaust survivors’ kids contained either higher or lower levels of cortisol than the offspring of parents who weren’t in the Holocaust. Cortisol is a hormone released from our adrenal glands that regulates stress, blood pressure, immune response, and inflammation. Both high and low levels of cortisol have been linked to psychiatric conditions, such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and major depression. Based on these findings, it’s possible that a generation later, children who weren’t directly exposed to the horrors of the Holocaust could still carry the remnants of that trauma in their blood from their parents. This landmark study has far-reaching implications for other populations marred by generational trauma, including the descendants of the transatlantic slave trade and war.

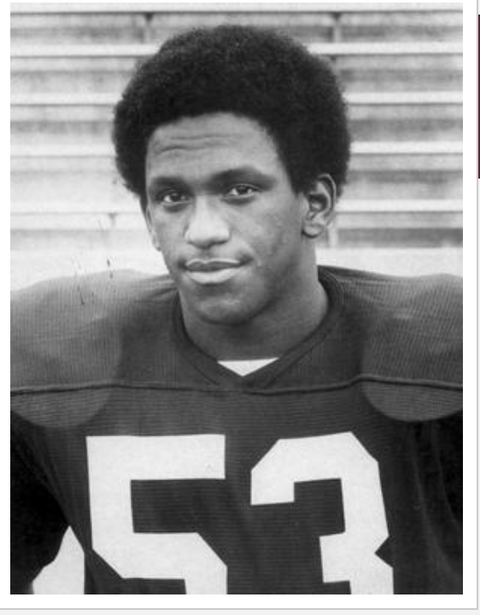

“Experience can change the way that your genes are regulated,” Yehuda told ELLE.com. “Those changes are probably meant to be helpful. But again, what is the context in which you’re living?” Genetically, mothers and fathers prepare their offspring for the world they will live in long before they are conceived. If a mother or father experiences prolonged trauma, the way their body responds to those life stressors can be encoded in epigenetic adaptations that are meant to help the child survive in the same conditions. For example, if my grandfather developed chronic stress and hypervigilance from boxing or being forced into war as a young man, it’s possible that his bloodline could carry the same protective stress response. My father, Roosevelt Kelly, was a rookie in the NFL, drafted by the Steelers in 1977, before he was forced into early retirement due to a career-ending injury to his left shoulder. As I reflect on my grandfather’s life, I’ve questioned if that legacy of hypervigilance aided my dad’s ability to be a professional athlete and if my boxing muscle spasms were linked to a family history of violent physical contact. “You might have this innate body wisdom from somewhere,” Yehuda told me. “Your body is fundamentally about adapting. However, sometimes we find ourselves with gifts we can’t use.” So, while a legacy of body defense might have made sense for my athlete father and war-trained grandfather, I must examine if I need those same tools to survive in the world I live in now. “The stress of hypervigilance does wear our neurological functioning down, and sometimes it can wear down our capacity for our bodies to even fight off disease and infection,” said Dr. Mariel Buqué, a Columbia University-trained holistic psychologist and best-selling author of Break the Cycle: A Guide to Healing Generational Trauma.

Dr. Buqué hopes we can make deep-level familial analysis like this more of the norm in non-white communities. “Often, these experiences that we have around our minds and bodies are very well-situated in historical experience,” she said. Karen Rose, a master herbalist and owner of Sacred Vibes Apothecary in Brooklyn, New York, told ELLE.com that uncovering a legacy of grief in her maternal bloodline helped her make sense of the heart issues that impact her family in the present-day. “I’ve always heard my mom talk about this history of folks on her side not having strong hearts,” Rose told ELLE.com. She said her aunt died from heart failure, and her mom had surgery to repair a heart valve as well. As Rose began following the trail of heart disease in her family, the breadcrumbs led to her Chinese great-grandmother, who left her family behind and immigrated from China to Guyana, where she was married to a Ghanaian man, according to Rose. Due to racial tensions, Rose said her great-grandmother was pressured to give up her children, because they were mixed race. Rose said whenever her great-grandmother was close to giving birth, she was sent to live in a different Caribbean country. After the baby was born, she was forced to leave her newborn child behind and come back to Guyana. This happened with two children. “I embody part of that heartbreak. And the lineage embodies part of that heartbreak, too,” Rose said.

Oluseyi Princewill, M.D., M.P.H., a board-certified cardiologist practicing in Maryland, told ELLE.com that there’s a condition called stress cardiomyopathy, which can affect how the heart pumps blood when subjected to extreme stress. She said life circumstances, like the death of a loved one or profound grief, can trigger heart dysfunction. She said that it’s not necessarily that we inherit our forefathers’ and foremothers’ heartbreak, but if your ancestors experienced chronic stress that impacted how their hearts functioned, as their offspring, you could be at greater risk of developing heart issues in the future. “If you’re exposed to enough stressors over time, and your family has an inclination or proclivity to develop heart disease, then that stress can ultimately be one of the factors that can lead to multiple family members having heart disease,” Dr. Princewell told ELLE.com. That’s why it’s important to know your family’s health history, including cases of stroke, heart attack, and high blood pressure, so that you can report any findings to your medical provider. Knowledge empowers us to devise preventive measures to stave off risk, including regular exercise and a nutritious diet.

In Buqué’s book, she explains that in many indigenous cultures, it is believed that up to “seven generations of sorrow” can live in the body. But as duality goes, that means we have the potential to embody seven generations of joy, too. So what do we do with what we learn about our bodies and their family histories? That’s a personal decision between you, your care providers, and your family. For me, it’s been therapy, acupuncture, breathwork, meditation, the chiropractor, and yoga. It’s a hell of a lot. Healing has been the most intense but rewarding journey I’ve ever traveled. Bringing deep awareness to the tense muscles on the left side of my body helps me to not only acknowledge my pain, but also to bring breath to the unprocessed exhales of those who came before me. For Rose, she said her work in herbalism, and specifically working with hawthorn flowers and linden plants, has helped soothe and bring trusting energy into her heart space. I’ve also started to find peace in the simple act of meditating on my own life, which so often bears the hidden footprints of my ancestors.

On my upper left shoulder, I have a tattoo of the Ghanaian Adinkra symbol Sankofa, which symbolizes the importance of returning to the past to gain knowledge for the future. As a teen, I made an impulsive decision after seeing the symbol repeated in the margins of a book I was reading by former Essence editor-in-chief Susan L. Taylor. This was long before I found out through blood testing that I have Nigerian, Mali, Cameroonian, and Ghanaian DNA in my blood. Perhaps the blueprint to my healing was tattooed on my skin the whole time. In the words of Jay-Z on Beyoncé’s track “Mood 4 Eva,” “True kings don’t die, we multiply.” And with triumph, I can confidently say, despite the genocide of slavery and subjugation to wars we didn’t start, we’re still here with the eye of the tiger—fighting and winning.